summary

- Researchers are experimenting with biosensors that can monitor workers’ vital signs and provide warnings if they show signs of heatstroke.

- The four-year study involves more than 150 farmworkers in Florida who have been wearing sensors in the fields.

- Agricultural workers are 35 times more likely to die from heatstroke than other workers.

People who work outdoors are at greatest risk from extreme heat, which can be fatal within minutes, so researchers have begun experimenting with wearable sensors that can monitor workers’ vital signs and warn them if they are starting to show the early symptoms of heatstroke.

In Pearson, Florida, where temperatures can soar to nearly 90 degrees just before and after noon, workers on a fern farm wear experimental biopatches as part of a study sponsored by the Environmental Protection Agency. National Institutes of HealthThe patch also measures a worker’s vital signs and skin hydration, and is equipped with a gyroscope to monitor continuous movement.

Scientists from Emory University and Georgia Tech are collecting data and feeding it into an artificial intelligence algorithm. The ultimate goal is for the AI to predict when workers are likely to suffer from heatstroke and send them a warning on their phone before that happens. But for now, the researchers are still analyzing the data and plan to publish a research paper next year.

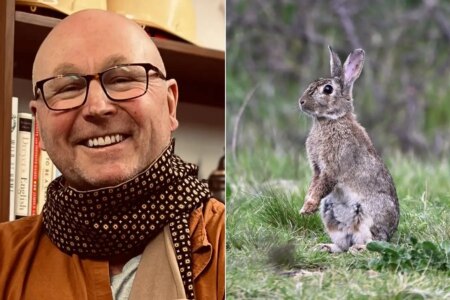

“There’s a perception that field work is hot, and that’s the reality,” says Roxana Chicas, a nurse researcher at Emory University who has been overseeing Biopatch data collection. “I think with research and creativity, we can find ways to protect field workers.”

average 34 workers died of heatstroke According to the Environmental Protection Agency, farmworkers will be killed every year from 1992 to 2022. 35x odds Workers are more likely to die from heatstroke than other workers, but until now it has been left to states to decide how to protect workers from heatstroke. California, for example, requires employers to provide training, water, and shade when temperatures exceed 80 degrees Fahrenheit, but many states have no such rules.

Chicas and his team partnered with the Florida Farmworkers Association to recruit participants for the study, aiming to have 100 workers wear the biopatch over the four-year study, but were surprised by how many volunteered, ultimately enrolling 166.

Participating workers arrive at work before dawn, receive a patch, have their vital signs monitored, and then head out into the fields before the hottest, most dangerous parts of the day.

“We hope this study will help improve working conditions,” study participant Juan Pérez said in Spanish, adding that he has worked in the fern fields for 20 years and would like more breaks and higher wages.

Other farmworkers said they hoped the study would shed light on just how tough their jobs are.

Study participant Antonia Hernandez, who lives in Pearson, said she often worries about the heat hazards facing her and her daughter, who both work in fern fields.

“When you don’t have a family, the only thing you worry about is the house and the rent,” Hernandez said in Spanish. “But when you have children, the truth is, there’s a lot of pressure and you have to work.”

Chicas said he could see the heat-related fatigue showing on some of the workers’ faces.

“They look much older than their real age, some of them look much older than their real age, because it takes a toll on their body and their health,” she said.

Chikas has been researching ways to protect farmworkers from the heat for nearly a decade. In a project that began in 2015, workers were fitted with bulky sensors that measured skin temperature, skin hydration, blood oxygen levels, and vital signs. This latest study is the first to test a lightweight biopatch that looks like a large bandage and is placed in the center of the chest.

Overall, wearable sensors are much easier to use, and some are becoming more widely used. While the biosensors that Cikas’ team is experimenting with aren’t yet available to the public, a brand called SlateSafety sells a system (sponsored by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration) that is available to employers. The system includes an armband that transmits measurements of a worker’s core temperature to a monitoring system. If the temperature is too high, the employer can notify the worker to take a break.

A similar technology, called the Heat Stroke Prevention System, is used in the military. Developed by the U.S. Army Institute of Environmental Medicine, the system requires soldiers or Marines in a company to wear a chest strap that estimates core temperature, skin temperature and gait stability, allowing commanders to understand a soldier’s location and risk of heatstroke.

“The system is programmed to sense when a person is approaching higher than appropriate levels of heat exposure,” says Emma Atkinson, a biomedical researcher at the institute. stated in a news release “Our system allows us to provide warnings before heat stroke occurs, allowing us to intervene before someone collapses,” the report, released in February, added.

The system that Chicas and his team are developing differs from those systems in that it notifies workers directly, rather than in a larger system controlled by their employers. They haven’t finished collecting data from farmworkers yet, but the next step is for algorithms to start identifying patterns that might indicate risk of heatstroke.

“Outdoor workers need to spend time outdoors – otherwise food wouldn’t be harvested, ferns wouldn’t be cut, houses wouldn’t be built,” Chicas said. “With the growing threat of climate change, workers need something to better protect themselves.”

Source: www.nbcnews.com