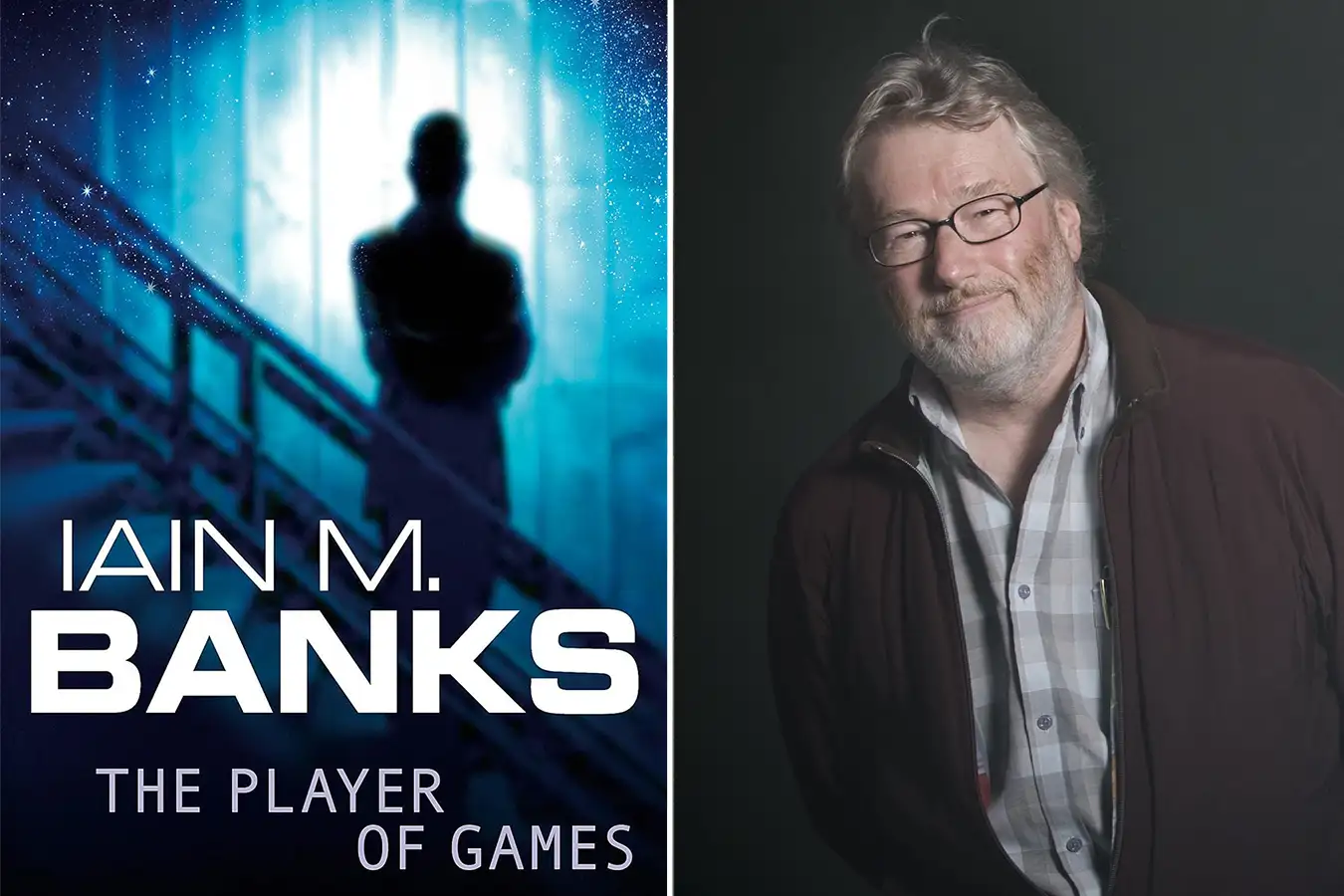

The Book Club explores The Player of Games by Iain M. Banks.

Colin McPherson/Corbis via Getty Images

The New Scientist Book Club has transitioned from Grace Chan’s dystopian near-future in Every Version of You to the utopian distant future depicted by Iain M. Banks in The Player of Games. This December’s book garnered positive feedback from our members.

Set within a vast galactic civilization, The Player of Games follows Gurgeh, a master gamer thrust into a conflict against the barbaric Azad Empire. This intricate game is so pivotal in Azad culture that the victor ascends to emperor. Though Gurgeh is a novice, can he rise to the challenge? What secrets lie between the Culture and Azad? This overview encapsulates member insights on the book, complete with spoilers. Proceed only if you’ve finished!

Remarkably, this wasn’t the first reading for many of us. Thirty-six percent of the group, including myself, acknowledged previous familiarity with this Banks classic. Many expressed nostalgia for Banks, lamenting the absence of new works from this literary giant. “I miss Ian. I haven’t yet delved into his final book, The Quarry. After this, there will be nothing new to experience!” lamented Paul Oldroyd in our Facebook group. “Similarly, I’m yet to complete The Hydrogen Sonata!” chimed in Emma Weisblatt.

While I consider myself knowledgeable about Banks’ works, The Player of Games felt refreshed in my memory. I found it immensely engaging; Banks’ subtle brilliance is captivating. For instance, I was intrigued by the Stigrian counting creature, which counts everything it encounters—starting with people, then transitioning to furniture.

There’s much to contemplate, from the essence of existence in a utopia devoid of challenges to the meaning of humanity in a realm governed by a vast intellect. The plot itself is thrilling! When Gurgeh faced temptation to cheat in a game against Mawhirin-Skel, I could hardly contain myself. The Azad games entirely captivated me. As a post-Christmas indulgence, I plan to reread more of Iain M. Banks’ works.

An exceptional aspect of the book was Banks’ portrayal of the game Gurgeh plays. Crafting a futuristic game and rendering it believable is no small feat. Banks excels here, providing enough detail about Azad to enhance realism without overwhelming the reader. Members also found this intriguing; Elaine Lee remarked, “The game of Azad is an expression of empire and serves as a critique of Cold War politics.”

Judith Lazell was less convinced, stating, “I viewed it simply at face value.” Nile Leighton aptly noted the deeper implications within the gameplay. “Critically, it’s a game where Gurgeh acts as a pawn under the narrator’s influence, lacking clear rules and enduring for decades, with unknowable outcomes.” Indeed!

As a footnote, during a chat with Banks’ friend and fellow sci-fi author Ken MacLeod, I learned he suggested the final title of the book. Banks initially titled it Game Player, which I believe is a more fitting title!

Now, let’s discuss the character of Gurgeh. “Gurgeh might not be likable without his cultural background. He is somewhat unsettling and self-absorbed. I hope he learns from his journey,” stated Matthew Campbell via email. I’m unsure if we’re meant to root for him—he’s an arrogant con artist—but my support grew as the story unfolded.

In contrast, Steve Swann found himself disengaged with the narrative. He “set the book aside” stating, “Intelligent individuals, particularly those who assume they are, can make serious blunders.” Steve felt Gurgeh’s arrogance and desires influenced his decision-making. What’s that saying? He had to make his bed and lie in it—no sympathy there!

Niall has a different view on Gurgeh’s choices. He perceives Gurgeh as manipulated by external forces, with Maurin-Skel tampering with his mind. “I interpret Gurgeh’s decisions as not entirely his own but a result of manipulation,” Niall explained. “To me, Gurgeh is not the master player; he is the one being played.” While I agree, I saw Gurgeh’s choice to cheat as a distinctly human reaction to seduction, sparking fascinating discussion.

Paul Jonas remarked that Gurgeh, as a character, lacked the compelling nature of the mercenaries in Consider Phlebas or Use of Weapons. “It’s part of the protagonist’s reluctance to embrace adventure,” he noted—after all, why would Gurgeh forsake comfort without motivation?

Our science fiction columnist, Emily H. Wilson, pointed out that The Player of Games serves as an excellent introduction to Iain M. Banks’ universe. The narrative reveals the Culture through subtle details about drones, spacecraft, and their orbits.

We gradually discover the workings of a post-scarcity society, where almost anything is achievable. I especially appreciated the exchange between Gurgeh and Azad elder Hamin about crime and societal norms. Hamin struggles to comprehend the lack of crime in the Culture, even as slap drones are designed for enforcement. “We will ensure you don’t repeat it,” Gurgeh assures. “Is that all? What more can you ask?” Hamin inquires. “Simply social death—no invitations to parties,” Gurgeh replies.

Paul Jonas was already familiar with the Culture’s utopian elements when he started The Player of Games. “[The book] subtly builds this world through Gurgeh’s ennui and lack of challenges. Anyone can secure a home atop a rainy mountain; the drones possess distinct personalities.” He adds, “The narrative also reintroduces Contact, an institutional service managing interspecies engagements, military affairs, and intelligence—an inherently humanistic approach to utopia.” Adam Roberts highlights that writing utopias becomes increasingly complex when the characters experience ennui, as Gurgeh does.

Some members reflected on the implications of living in such a utopia. “Gurgeh is an individual navigating an individualistic utopia dominated by minds, drones, and sentient ships,” Paul theorizes. “He seems disconnected from collaboration with fellow humans.”

Niall noted that while Gurgeh may come off as “unpleasant,” he embodies the consequences of the anarchist society he inhabits and that Banks delves into the nuances of individualistic and collectivist perspectives. “Gurgeh exemplifies individualism. I critique it, as it often excuses behavior akin to Gurgeh’s,” Niall states. It’s worth noting that while this book predates Octavia Butler’s emphasis on change within utopias, the conversation has existed since H.G. Wells.

Matthew Campbell identified Azad’s cultural ambassador, Shokhobohaum Za, as the only character “truly alive and reveling in life.” “In contrast, Gurgeh and the Azadians remain trapped within their isolated worlds,” he reflects. The rivalry between Emperor Nicosar and Gurgeh encapsulates contemporary political dilemmas—one figure exuding passion for his empire but constrained by a narrow worldview, while the other lacks belief and conviction, failing to defend his utopia.

The insights on culture and the ethos of The Player of Games are boundless. To further engage in this discussion, feel free to join us on Facebook.

Meanwhile, we look forward to our first reading of 2026. Our January selection, Anniebot by Sierra Greer, has already won the 2025 Arthur C. Clarke Science Fiction Award. Narrated from the perspective of a sex robot, Annie, who is kept by a not-so-nice man, this novel ventures into darker territories. Andrew Butler, chair of the Clarke Prize jury, described it as a “tightly focused first-person account of a robot designed to be the perfect companion struggling for independence.” You can check out an excerpt here. Additionally, Sierra Greer’s article detailing the experience of writing from a sex robot’s viewpoint is available here. Not to mention, Emily H. Wilson praised it in her review—she found it captivating!

Topics:

Source: www.newscientist.com