The Last of Us is a story of tension: between love and loss, violence and intimacy, protection and destruction, life and death. It’s also a study in how fragile life can be and the terrible stubbornness of the will to survive. As a composer, Gustavo Santaolalla’s job was to navigate that tension and create a soundtrack, a reconciliation between the game’s conflicting themes. His mission was to compose music for a video game that was doing something different and really wanted to say something.

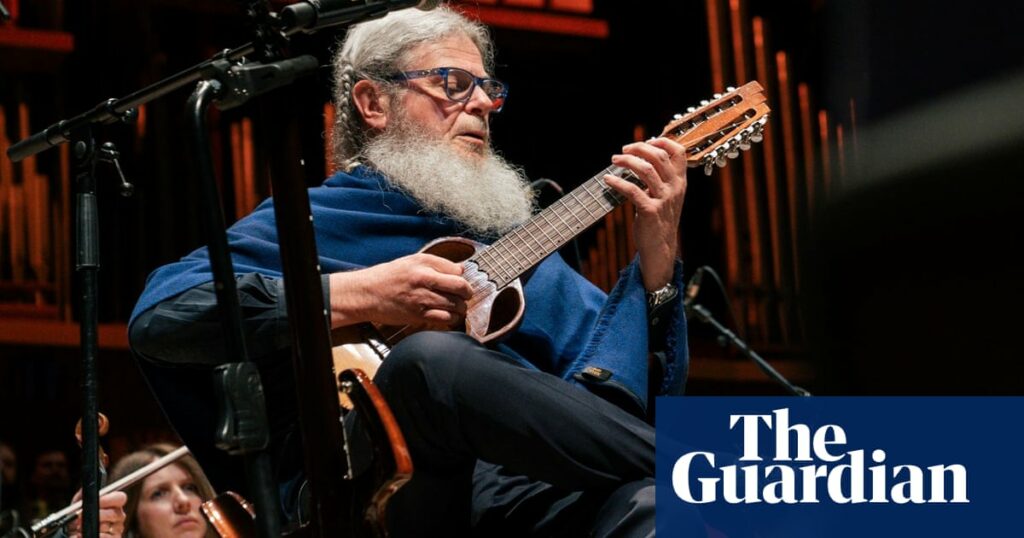

Santaolalla shared with me that as a child in rural Argentina, one of his tutors quit after only a few lessons, telling his parents, “I can’t teach you anything.” His career began in 1967, when he co-founded Arco Iris, a band that specialized in fusing Latin American folk and rock. After a brief stint leading a collective of Argentine musicians in Soluna, he went independent, releasing solo albums and beginning to compose for television shows, advertisements, and eventually films (most notably Amores Perros, 21 Grams, and The Motorcycle Diaries).

In 2006 and 2007, he won Academy Awards for his performances in Brokeback Mountain and Babel, respectively. Now a big name in Hollywood, he was headhunted by many TV and film directors and producers, as well as game developers, in the years that followed.

“After I won the Oscar, I was approached by a few companies to do music for video games,” Santaolalla recalls. “A European company approached me to do a Western video game. It was going to be a big project, financially, in terms of visibility and what it could represent, but it was all pretty similar. I wanted to do something that would connect emotionally with what I was doing in the game, something more than just gymnastics or shooting or fighting or surviving.”

Santaolalla was approached by Naughty Dog around 2009, early in the game’s development, to work on The Last of Us. The story is about an orphaned girl named Ellie and a man named Joel who is grieving the loss of his daughter. Set against the backdrop of a zombie apocalypse, the two slowly open up and show each other their weaknesses. The closer the two protagonists get, the more they hurt each other, depicting a complicated hedgehog dilemma relationship.

It was perfect for Santa Olaya, who was able to bring his Argentinian-inspired soulfulness to a non-Western setting, imbuing the urban ruins of Boston, Massachusetts, with an Americana vibe that was dreamy and familiar, yet distinctly American. Even the way he plays his guitar, scraping and scratching the strings with the pads of his fingers, suits the instrument’s understated humanity.

The soundtrack’s greatest attraction is the captivating interplay between Santa Olaya’s signature instrument, the Bolivian guitar, the Ronroco, and the Fender VI, a six-string bass guitar from the ’60s that sounds an octave lower than a guitar and a bit different from a modern bass. Listen to any song on the soundtrack and you can hear the gentle conversation between the two instruments, quiet but constant, sometimes agreeing, sometimes disagreeing.

The bass, famously used on Beatles and Cream records, is Joel’s voice; and the more delicate but no less powerful Ronroco is Ellie’s voice. “This six-string bass is definitely the masculine side of this story,” Santaolalla tells me. “And Ronroco, the delicate side of the music, is Ellie’s side of the story. I didn’t think of it that way when I wrote the song, but listening to it again, it’s so clear to me.”

“And the banjo and electric guitar fill the middle, the central role between these two extremes. As the story unfolded in Part II and we started introducing more characters and complexities, the music needed a richer tone. We couldn’t just stick to the combination we used in the first game.”

Everything Santaolalla does is “instinctive,” he says. He spontaneously introduced the banjo to Abby’s theme in The Last of Us Part II, and it was a perfect fit. He wasn’t born a banjo player, so using the instrument in his score feels foreign to his ears, searching, reflective, pensive. “I got out of bed one day, picked up my banjo, and it just came out of me,” he laughs. “Some of the character themes are magical in the way they happen. They come out when I’m not really thinking about it. I pick up an instrument, and it’s like someone else is playing it.”

The 72-year-old has an intuitive feel for his scores and knows that as a listener, his emotional response comes both from “what I hear” and “from what I actually hear.” and “What you can’t hear” is one of the reasons why The Last of Us’ score stands out. Game music is full of extremes: soaring bombast, orchestral high notes, intensity. The Last of Us is quite different, more introspective and quiet, expressing as much through the absence of music as through melody. The HBO TV series he composed for follows the same principle.

“I love using silence,” Santaolalla enthuses. “I love it. I love the space silence gives, because it gives resonance to the sounds you play around it.” Suddenly, he begins talking about parkour, a recent new interest of his, sparked by a group of British athletes. Stoller.

“I linked the jumps in parkour to the silence of music, and I think that’s really important,” he says. “Runners measure their jumps, they run, and they measure again before they jump, right? They measure their jumps, they decide how many steps they’re going to take before they put their feet on the ground and jump. It’s like choosing a note to play before you get quiet, before you jump. And you choose a note to play when you land, and with that note silence wins. You don’t fall. You’re in that space, in that moment of silence, and when you land it all makes sense.”

This interview, the master class he taught, and Game Music Festival I spent a fair bit of time with Santaolalla at his concert at London’s Southbank Centre. The way his brain works, and the way he connects concepts to practice, is inspiring. When he performed “Ando Rodando,” a song from his 1982 album, Santa OlayaThe show is now dedicated to Joel for its “gritty, rock” nature, and the room was met with stunned silence. That Santaolalla was able to find traces of The Last of Us characters deep within his previous work and bring them into his performance demonstrates his deep understanding and love for Naughty Dog’s work.

Source: www.theguardian.com