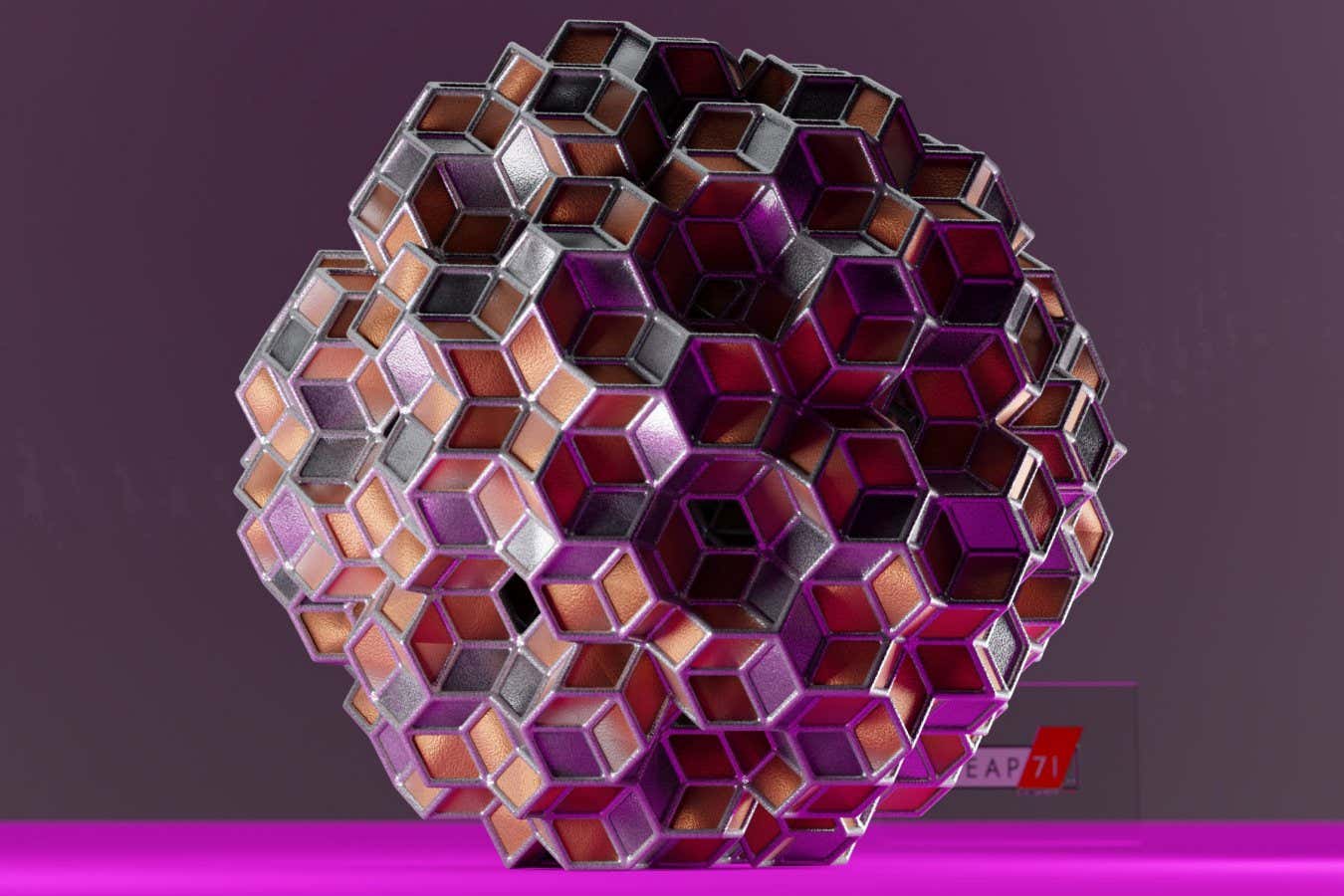

Visualization of quasicrystal structures

Linkayaser, Alexey E. Madison, Picogk, Leap? 71 CC BY-SA 4.0

Quasicrystals may be unusual, but recent research reveals they are also the most stable arrangements for certain atoms, shedding light on their existence.

In standard crystals, atoms align in orderly grids, showcasing high stability; whereas in glass—like common glass or volcanic obsidian—the atoms are disarrayed. Glasses are termed metastable, meaning they can evolve due to environmental shifts such as heat or impurities from unwanted atoms. Given ample time, glassy structures can ultimately crystallize.

Quasicrystals occupy a unique middle ground: their atoms are arranged in non-repeating patterns, raising long-standing questions about their stability.

Wenhao San from the University of Michigan and his team are utilizing advanced computer simulations to investigate these structures. They examined two specific quasicrystals composed of scandium and zinc, and another featuring ytterbium and cadmium, simulating large quasicrystalline nanoparticles. Throughout their analysis, they measured the energy dynamics of these quasi-crystals in comparison to more conventional crystal structures.

The principles of physics suggest the most stable formations derive from atoms with the least collective energy, which the researchers found to be true. They discovered quasicrystals preferred due to their lower energy sustenance compared to typical atomic arrangements.

Sun expressed this finding as somewhat unexpected, noting that contrasting quasicrystals with glass can lead physicists to assume they are metastable. The innovative simulation techniques previously posed challenges, as they usually predicted a completely regular atomic arrangement, according to team member Vikram Gabini from the University of Michigan. Their fresh computational methods demonstrated that quasicrystals require very specific conditions to grow in laboratory settings.

“Quasicrystals exhibit remarkable vibrational characteristics that relate to thermal conductivity and thermoelectric effects. New methodologies might enhance our understanding of them,” remarked Peter Brommer from Warwick University, UK. “It’s possible the next breakthrough material will emerge from simulations rather than physical laboratories.”

Topic:

Source: www.newscientist.com