Paleontologists studied fossils that are 160 million years old. Anchiornis Huxley, a non-avian theropod dinosaur, was unearthed from the Late Jurassic Tianjishan Formation in northeastern China. The preserved feathers indicated that these dinosaurs had lost their flying capability. This rare find offers insights into the functions of organisms that existed 160 million years ago and their role in the evolution of flight among dinosaurs and birds.

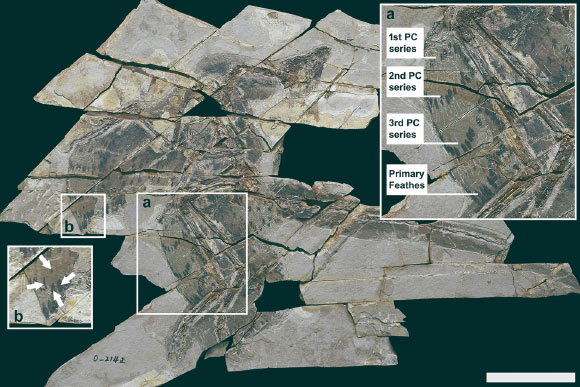

This fossil of Anchiornis Huxley has nearly complete feathers and coloration preserved, allowing for detailed identification of feather morphology. Image credit: Kiat et al., doi: 10.1038/s42003-025-09019-2.

“This discovery has significant implications, suggesting that the evolution of flight in dinosaurs and birds was more intricate than previously understood,” said paleontologist Yosef Kiat from Tel Aviv University and his team.

“It is possible that some species had rudimentary flight abilities but lost them as they evolved.”

“The lineage of dinosaurs diverged from other reptiles approximately 240 million years ago.”

“Shortly after (on an evolutionary timeline), many dinosaurs began developing feathers, unique structures that are lightweight and strong, made of protein, and primarily used for flight and thermoregulation.”

About 175 million years ago, feathered dinosaurs, known as Penaraputra, emerged as distant ancestors of modern birds; they are the only dinosaur lineage that survived the mass extinction marking the end of the Mesozoic Era 66 million years ago.

As far as we know, the Pennaraputra group developed feathers for flight, but some may have lost that capability due to changing environmental conditions, similar to modern ostriches and penguins.

In this study, the researchers examined nine specimens of a feathered pennaraptorian dinosaur species called Anchiornis Huxley.

This rare paleontological find, along with hundreds of similar fossils, had its feathers remarkably preserved due to the unique conditions present during their fossilization.

Specifically, the nine fossils analyzed were selected because they retained the color of their wing feathers: white with black spots on the tips.

“Feathers take about two to three weeks to grow,” explains Dr. Kiat.

“Once they reach their final size, they detach from the blood vessels that nourished them during growth and become dead material.”

“Over time, birds shed and replace their feathers in a process known as molting, which is crucial for flight.” He notes that birds that depend on flight molt in an organized and gradual manner, maintaining symmetry and allowing them to continue flying during the process.

Conversely, the molting of flightless birds tends to be more random and irregular.

“Molting patterns can indicate whether a winged creature was capable of flight.”

By examining the color of the feathers preserved in dinosaur fossils from China, researchers could reconstruct the wing structure, which featured series of black spots along the edges.

Additionally, newly grown feathers, which had not fully matured, were identifiable by their deviation in black spot patterns.

A detailed analysis of the new feathers in nine fossils revealed an irregular molting process.

“Based on our understanding of contemporary birds, we identified a molting pattern suggesting these dinosaurs were likely flightless,” said Dr. Kiat.

“This is a rare and particularly intriguing discovery. The preservation of feather color offers a unique opportunity to explore the functional characteristics of ancient organisms alongside body structures found in fossilized skeletons and bones.”

“While feather molting might seem like a minor detail, it could significantly alter our understanding of the origins of flight when examined in fossils,” he added.

“Anchiornis Huxley‘s inclusion in the group of feathered dinosaurs that couldn’t fly underscores the complexity and diversity of wing evolution.”

The findings were published in the journal Communication Biology.

_____

Y. Kiat et al. 2025. Wing morphology of Anchiornis Huxley and the evolution of molting strategies in paraavian dinosaurs. Communication Biology August 1633. doi: 10.1038/s42003-025-09019-2

Source: www.sci.news