Here’s a rewritten version of the content while preserving the HTML tags:

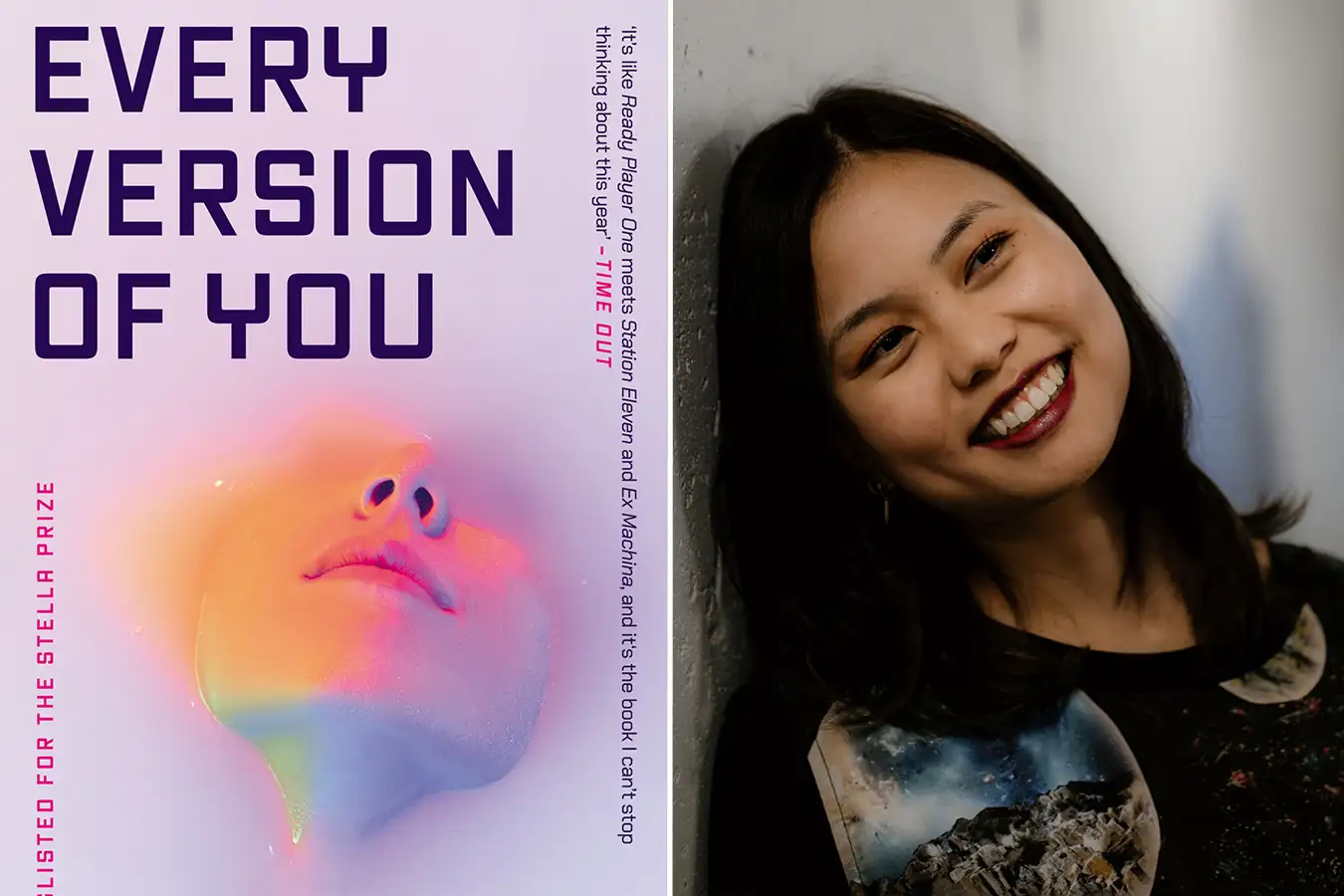

Every Version of You by Grace Chan was the November selection for the Emerging Scientist Book Club

The New Scientist Book Club delved deeper into the complexities of the mind during its November selection, transitioning from neurologist Masud Hussain’s insights on brain damage to Grace Chan’s thought-provoking exploration in Every Version of You, which imagines a reality where individuals upload their consciousness to a digital utopia.

Follow the story of Tao Yi and her boyfriend Navin—among the pioneers who have transitioned their minds to Gaia, a digital haven, even as it faces the repercussions of climate change. Every Version of You captivated my fellow book club members, myself included, as it tackled profound themes such as humanity, the essence of home, climate change, and the process of grieving.

“It was an incredible experience. Probably the best choice the club has ever made,” stated Glen Johnson in our Facebook group. “My familiarity with Avatar extends only to the first movie, so… [I] found the beginning a little perplexing,” shared Margaret Buchanan. “While I resonate with the desire to escape the chaos we’ve created on Earth, I found Tao Yi’s struggle to hold onto her identity very relatable.”

Judith Lazell found the novel to be “very enjoyable” and noted her admiration for Chan’s portrayal of the realities faced by a young adult in 21st-century Australia.

However, with our book club comprising over 22,000 members, positive feedback wasn’t universal. “I loved the book, but the ending felt unclear,” remarked Linda Jones, and Jennifer Marano expressed her dissatisfaction with certain plot elements. “The environmental crisis depicted was quite distressing,” she conveyed. “After finishing, I felt unfulfilled. There was an implication that humanity’s upload to Gaia could allow regeneration back on Earth, yet there was no explanation of how the failing digital world they escaped was maintained.”

Every Version of You lingered in my thoughts for months (I revisited it in May), prompting contemplation on the ethical dilemma of uploading my consciousness. As Chan mentioned in an interview, I’ve leaned toward the belief that it’s not a viable option for me, though discussions around this are ongoing within the group. “In the current state of our world, no, but if we faced the same degradation as in this novel, my stance might shift,” reflected Steve Swan.

Karen Sears offered a unique perspective on the topic. “Initially, I resolved to hold off on uploading until I fully understood Gaia’s framework, politics, and protocols,” she explained. “Then, after injuring my knee, my outlook transformed a bit. It made me reconsider how I would feel about staying in a world that became increasingly difficult to navigate.”

One element I appreciated in the book was its sensitive treatment of disability through Navin’s struggles in reality, which fueled his desire for the escape that Gaia represented. This was approached with care, as noted by Niall Leighton.

“It’s commendable that Chan addresses disability and marginalization issues (especially given some past criticisms of her work!), but I’m curious to see if she has even deeper insights,” noted Niall in response to Karen. “If we question the continuity of consciousness, what does the choice to upload truly signify? Today’s significant dilemmas revolve around alleviating physical and psychological suffering and the societal structures that render life challenging for individuals with disabilities.”

Niall’s review of the book featured an acknowledgment of his mixed feelings: I will write, he suggested, that “this multi-dimensional narrative tackles numerous contemporary issues, engaging my intellect and meeting my expectations for a compelling sci-fi tale. Grace Chan exhibits a strong commitment to plot and character development.” However, he contrasted it with his personal preferences, stating, “It falls within the ongoing trend of publishing a seemingly unquenchable thirst for novels that plunge us into dystopian realities.”

This sentiment has resonated with a few members, expressing it’s not merely another dystopia. “While it’s readable, I can’t say I particularly enjoyed it. It leans towards a dystopian vision of the future, and we’ve encountered several of those this year—Boy with Dengue Fever and Circular Motion,” noted David Jones.

Phil Gursky shared that the book “impressed itself upon my heart over time (initially, I wasn’t sure I’d finish it).” He found it a familiar narrative of a world succumbing to climate change, yet it kept him engaged. “A quick aside: A reality where everyone is perpetually online reminds me of my commute on the O-train in Ottawa, where I was the only one engrossed in a physical book instead of fixated on my phone!” Note to Phil: I too notice fellow readers on the London Underground, grateful I’m not alone.

Members have mentioned their desire to avoid another dystopia. However, science fiction often envisions futures, presenting compelling contrasts to our current existence. We hope our December selection resonates with you, even as it incorporates a utopian theme: Ian M. Banks’ Game Player, following another of his works, Consider Phlebas, in our book club vote. Set in a multicultural interstellar landscape of humans and machines, it follows the formidable Jernau Morat Gurge, a gaming champion challenging the merciless Azad Empire in a notoriously intricate game, with the victor crowned emperor.

Here’s an excerpt from the beginning of the novel, along with an intriguing analysis by Bethany Jacobs, a fellow sci-fi writer and admirer of Banks, who delves into his exceptional world-building capabilities. And please join our Facebook group, if you haven’t already, to share your insights on all our readings.

Topics:

- Science Fiction/

- New Scientist Book Club

This retains all HTML tags while rephrasing the original content.

Source: www.newscientist.com