Since the 1980s, seismic observatories have detected increases in the strength of ocean waves that correlate with climate change. A Colorado State University study analyzed more than 35 years of data and found that ocean waves are becoming significantly stronger, reflecting the increased intensity of storms due to global warming. This seismic data reveals long-term trends and changes in wave energy and highlights the need for resilient strategies to protect coastal regions from the effects of climate change.

Since the late 1980s, modern digital seismic observatories have been monitoring Earth’s vibrations around the world. Previously thought by seismologists to be just a background disturbance, the persistent low hum produced by ocean waves has become stronger since the late 20th century, according to a study led by Colorado State University.

This research nature communicationsexamines data from 52 seismic stations that recorded the Earth’s movement once a second over 35 years. This decades-long record supports independent climate and ocean research that suggests storms are becoming more intense as the climate warms.

“Seismology can provide stable, quantitative measurements of what is happening to waves in the world’s oceans, complementing research using satellites, oceanography, and other methods.” said author Rick Astor, professor of geophysics and chair of Earth Sciences at CSU. “The seismic signal is consistent with these other studies and shows the types of features expected from anthropogenic climate change.”

Astor and his collaborators at the U.S. Geological Survey and Harvard University studied first-order microseisms, the seismic signals produced by large, long-period waves that cross shallow regions of the world’s oceans. The ocean floor in coastal areas is constantly being pushed and pulled by these waves, and these pressure changes generate seismic waves that are picked up by seismometers.

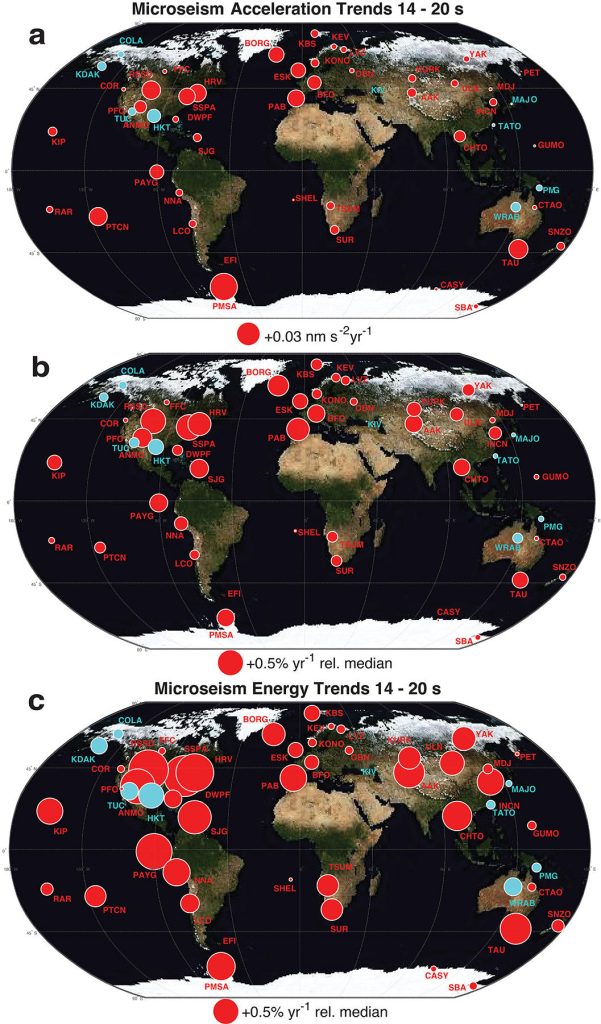

Seismic station locations and global trends since the late 1980s: (a) Ground vertical acceleration amplitude in billionths of a meter, (b) Acceleration amplitude normalized to the historical median, and ( c) Normalized by the historical median of seismic energy.Credit: Rick Astor

Seismometers are best known for monitoring and studying earthquakes, but they also detect many other things, including the movement of glaciers, landslides, volcanic eruptions, large meteorites, and noise from cities. Seismic waves from various forces on or within the Earth’s surface can be seen at great distances, sometimes even on the other side of the Earth.

“As the atmosphere and ocean warm, storms become more intense because they contain more energy, and the ocean waves they cause increase in size and energy,” Aster said. “Increasing the energy of ocean waves directly increases the strength of seismic waves.”

make (bigger) waves

Seismic signals show that the Southern Ocean waves of the infamous storm around Antarctica are predictably the most intense on Earth, while the waves in the North Atlantic are the most rapidly intensifying in recent decades, with waves in eastern North America and western Europe It reflects the storm that rages between.

In addition to the steady rise in wave energy that reflects widespread increases in global ocean and air temperatures, the data also show multi-year climate patterns such as El Niño and La Niña that influence the strength and distribution of global storms. Masu. And an even bigger storm.

“It’s clear that these long-term earthquake records show general signs of storm activity around the world, in addition to long-term intensification due to global warming,” Astor said. “It looks like a small signal from year to year, but it’s gradual and becomes very clear when you work with more than 30 years of data.”

Astor and his colleagues found that global average ocean wave energy has increased by a median of 0.27% per year since the late 20th century, and by 0.35% per year since January 2000.

Stormy weather forecast

Mr Astor said storm surges associated with larger waves and larger storms, coupled with rising sea levels, were a serious global problem for coastal ecosystems, cities and infrastructure.

“In addition to efforts to mitigate climate change itself, we will need to implement resilient strategies to ensure coastal populations and ecosystems are protected from an increasingly stormy future.” said Astor.

Reference: “Increase in ocean wave energy observed in Earth’s seismic wave field since the late 20th century” by Richard C. Astor, Adam T. Ringler, Robert E. Anthony, and Thomas A. Lee, October 32, 2023 , nature communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-42673-w

This research was funded by the U.S. Geological Survey and the National Science Foundation.

Source: scitechdaily.com