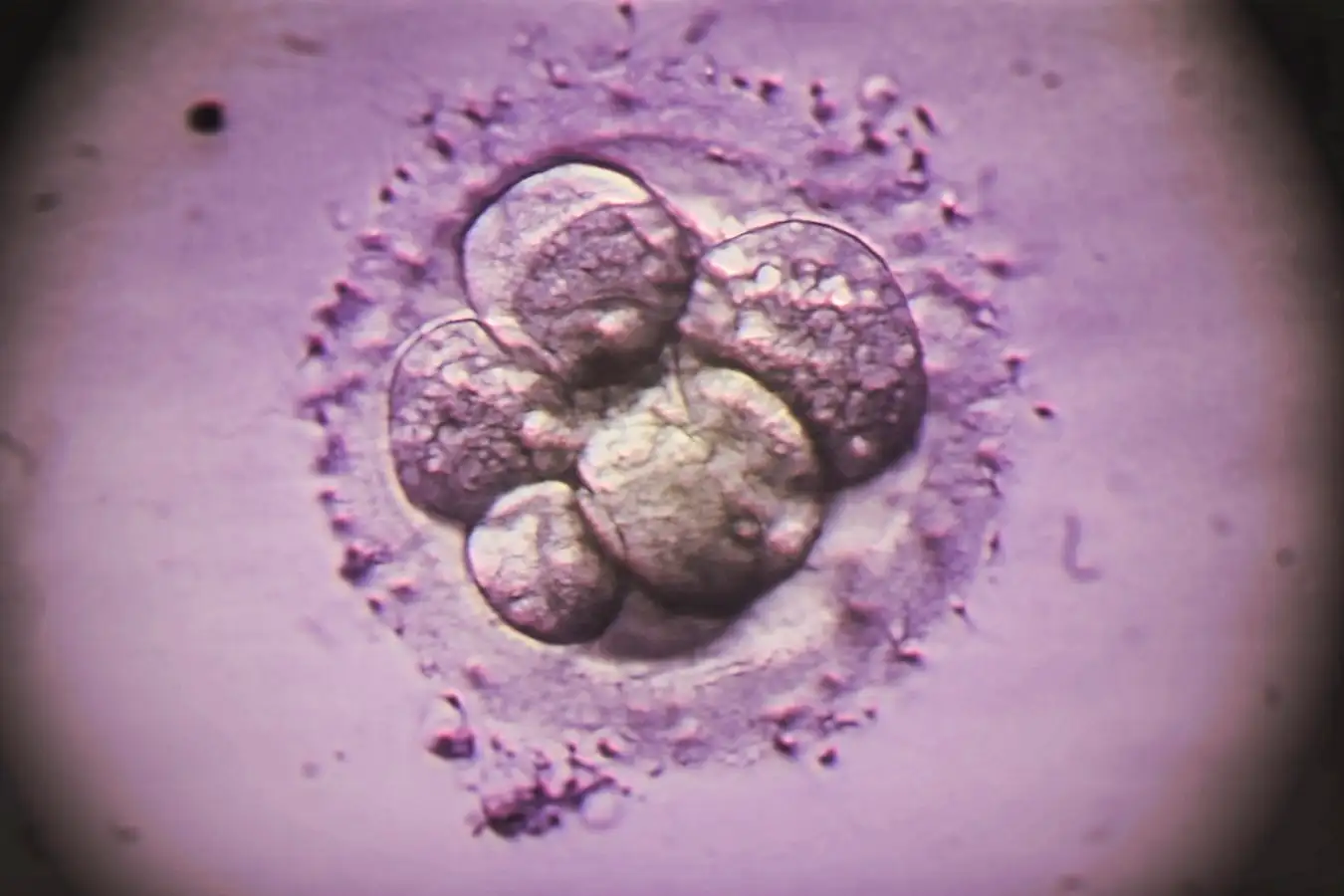

Colored light micrograph of a human embryo following in vitro fertilization

Zephyr/Science Photo Library

During in vitro fertilization (IVF), embryos are subjected to genetic screening prior to being placed in the uterus. Recent studies, however, have shown that the common tests may fail to identify genetic abnormalities arising shortly before implantation. The implications for choosing embryos that are likely to lead to a healthy pregnancy remain uncertain.

This process, known as preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A), is conducted about 5 to 6 days after fertilization. It involves extracting cells from the embryo’s outer layer to assess for chromosomal irregularities, which can elevate the risk of miscarriage. However, this testing only captures a moment in time, as cellular division continues and may introduce genetic changes prior to implantation.

To address this gap, Ahmed Abdelbaki and his colleagues at the University of Cambridge monitored the progress of human embryos 46 hours post-thawing, replicating the timeline from evaluation to implantation. Typically, the embryo takes 1 to 5 days to implant after being transferred to the uterus. Given that embryos are highly sensitive to the light from traditional microscopes, prior studies only managed to observe them for about 24 hours. The research team employed light-sheet microscopy, a technique that illuminates only a thin slice of the embryo at once, minimizing light exposure and enabling longer observation durations.

In their experiment, the researchers injected 13 human embryos with a fluorescent dye that attaches to DNA, facilitating real-time tracking of genetic abnormality formation. They recorded the division of 223 cells and discovered that 8% exhibited chromosomal misalignment. This misalignment occurs when chromosomes improperly arrange themselves before cell division, significantly raising the likelihood of creating cells with abnormal chromosome counts, potentially hindering implantation, increasing miscarriage risk, and leading to conditions such as Down syndrome.

This indicates that genetic changes might arise later. “These variances appear in the embryo subsequent to PGT-A screening,” stated Lily Zimmerman from Northwell Health in New York.

These chromosomal errors were restricted to the outer cell layer responsible for forming the placenta, rather than the central cells that mature into the fetus. Previous findings suggest that successful pregnancies can occur even with certain genetic abnormalities in the outer cells. Thus, Abdelbaki posits that these genetic errors may not detrimentally impact the embryo’s survival chances.

“In my view, this study highlights the necessity for further research in embryo screening. It’s not simply a matter of categorizing embryos as genetically normal or abnormal,” commented Professor Zimmerman. She also noted that it remains unclear how genetic alterations occurring between screening and implantation might influence embryo viability, and given that the study examined only a small sample of embryos, the broader applicability of these findings is uncertain.

Topics:

Source: www.newscientist.com