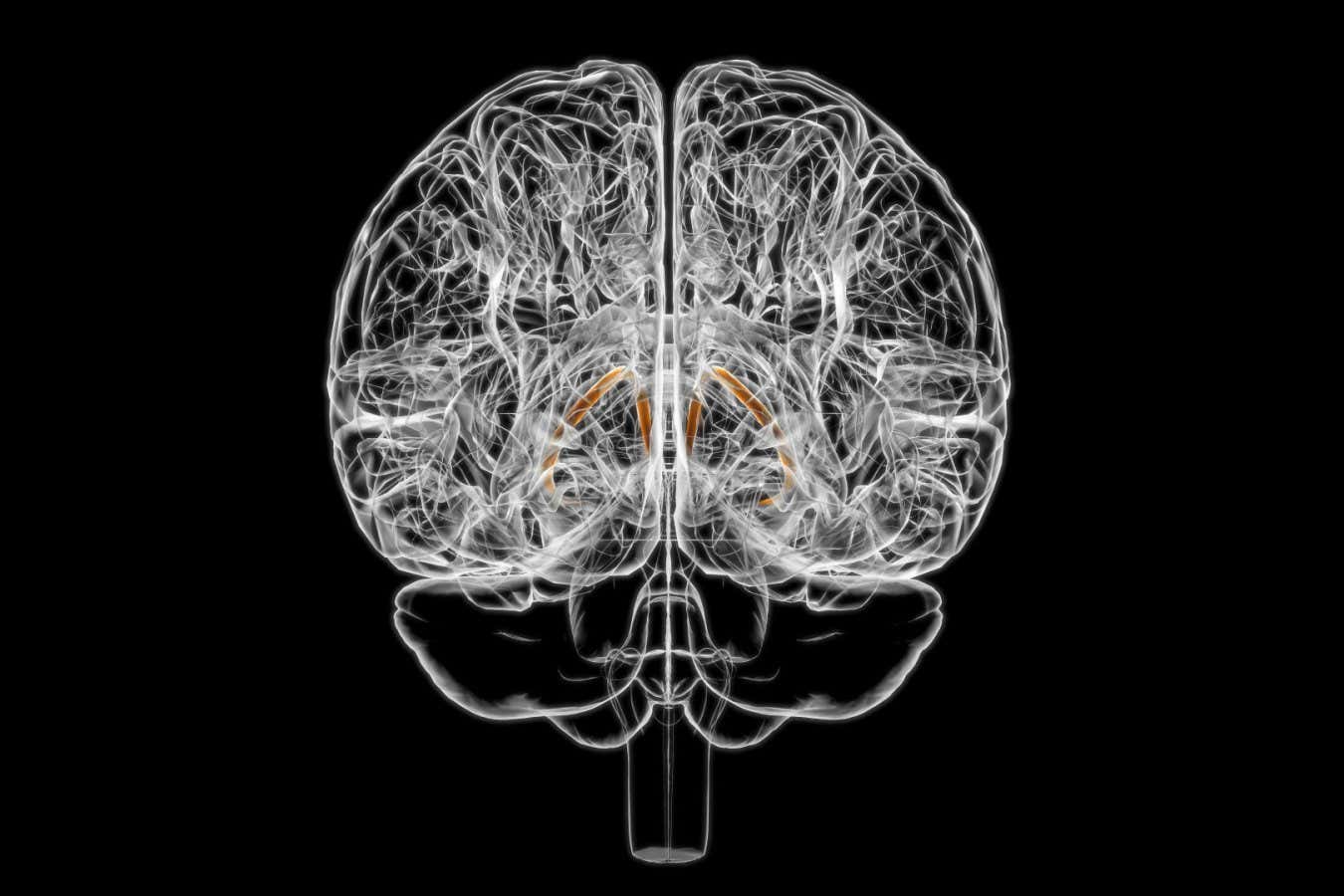

The bed nuclei of the stria terminalis comprise a larger, banded structure in the brain known as the stria terminalis.

My Box/Alamy

Brain regions that influence food intake may eventually be targeted to enhance weight loss or therapeutic interventions.

Studies indicate that activating neurons in this specific brain region leads to increased food intake in mice, particularly when consuming sunflower seed-sized food items. However, the impact of taste on neuronal activity remained ambiguous.

For deeper insights, refer to Charles Zuker from Columbia University, who, along with his team, conducted brain imaging on mice. Earlier research linked sweet taste neuron activity in the amygdala with the enjoyment of sweet substances.

These neurons stimulate other neurons in the BNST, sometimes referred to as the “expanded amygdala.” This marks the first evidence of taste signal reception by this brain structure, according to Haijiang Cai from the University of Arizona, who was not part of the study.

The researchers aimed to determine whether these activated BNST neurons influence dietary choices, so they genetically modified cells to prevent activation when mice tasted sweet substances. Over a 10-minute period, these modified mice exhibited significantly reduced consumption compared to their normal counterparts, indicating that BNST neuron activation encourages sweet taste consumption.

Interestingly, the researchers also discovered that this artificial activation led mice to consume more water and even seek out salty or bitter substances, which they typically avoid.

Further experiments indicated that more BNST neurons were activated by sweet and salty tastes in hungry or salt-depleted mice, suggesting that the BNST integrates taste signals along with nutrient deficiency cues to regulate food intake, according to Cai.

Given the similarities between human and mouse BNST, these findings are relevant for humans, says Cai. They suggest that developing drugs to activate BNST neurons could aid individuals experiencing severe appetite loss, like those undergoing cancer treatment.

Cai mentioned that numerous brain pathways regulate food intake, and some may compensate for long-term changes in BNST activity induced by drugs. Therefore, targeting multiple feeding circuits would likely be necessary.

This research also has implications for improving results from weight loss treatments, including the GLP-1 drug semaglutide. This drug binds to neurons in the BNST, and a clearer understanding of its effects on food consumption could enhance the effectiveness of such medications, according to Sarah Stern from the Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience.

Topic:

Source: www.newscientist.com