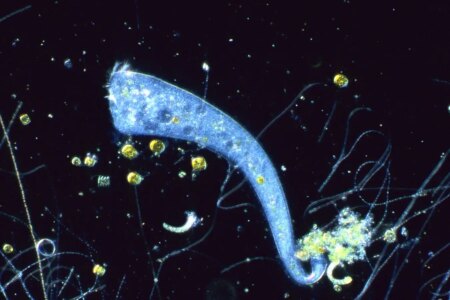

Bearded seals have complex nasal bones that help retain internal heat.

Ole Jorgen Rioden/naturepl.com

Arctic seals have evolved clever adaptations to help them stay warm in frigid climates. The nose has a complex maze of bones.

Many birds and mammals, including humans, have a pair of thin, porous nasal bones called turbinates or nasal turbinates, which are covered with a layer of tissue.

“They have a scroll shape or a tree-like branching shape,” he says. Matthew Mason at Cambridge University.

When we breathe in, air first flows through the maxillary turbinates, allowing the surrounding tissues to warm and humidify the air before it reaches the lungs. When we exhale, the air follows the same route, trapping heat and moisture so it doesn’t get lost.

The more complex the shape, the larger the surface area and the more efficient it is at doing its job.

Animals that live in cold, dry environments, such as arctic reindeer, have been found to have more complex gnathonasal turbinates than animals that live in warmer climates.

Now, Mason and his colleagues have discovered that arctic seals have the most complex gnathonasal turbinates ever reported.

Researchers took a CT scan of a bearded seal (Elignathus barbatus), commonly found in the Arctic, and the Mediterranean monk seal (monax monax). Both species had complex turbinates, but the researchers found that the bearded seal’s nasal bones were much denser and more complex than anything seen before.

Mason and his colleagues used computer models to measure how much energy is lost as heat in physical processes at -30°C and 10°C (-22°F and 50°F). We compared how well the seals retain heat and moisture.).

With each breath at -30°C, Mediterranean monk seals lost 1.45 times more heat and 3.5 times more water than bearded seals. Similarly, at 10°C, monk seals lost about 1.5 times more water and heat than arctic seals.

“More complex structures evolved to make life in the Arctic possible,” he says. Sign Kelstrup At the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

topic:

Source: www.newscientist.com