Far from the shore, in the immense stretches of the open ocean, resides an uncommon assembly of creatures known as “Neustons.”

This environment is a vast, two-dimensional layer of the ocean that bridges the atmosphere with the sea.

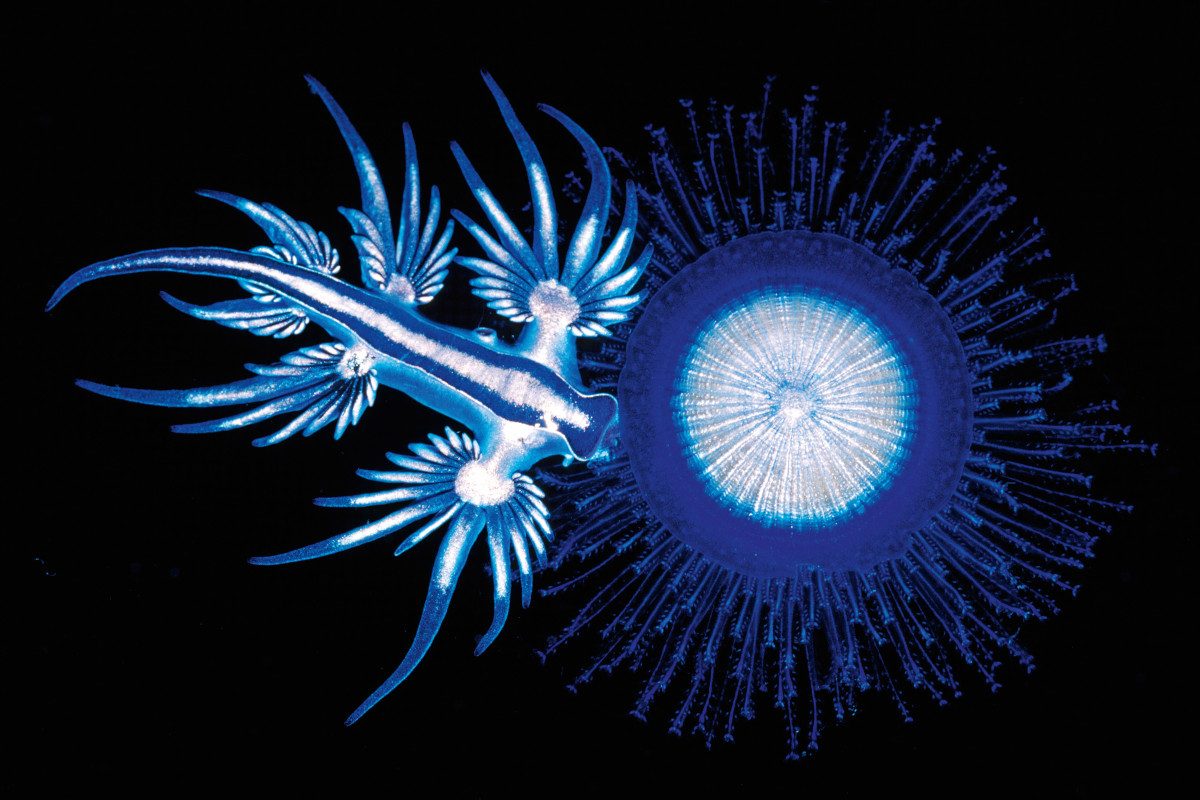

Among this group, one of the most fascinating beings is the blue dragon, a kind of sea slug, or naujibrance, more widely recognized as the blue dragon, the sea swallow, or Glaucus atlanticus.

Blue dragons float on the surface, buoyed by the air bubbles they have ingested. To evade predators, they employ a unique biological strategy called countershading.

The underside of their body, positioned upside down, exhibits a bright blue hue that camouflages it against the ocean below, concealing it from aerial hunters above.

Conversely, the side that hangs from the surface boasts silver stripes that mimic the shimmering ocean surface, aiding swimming predators in their upward gaze.

Overall, the blue dragon appears peculiar owing to its sea slug nature. The main body, measuring about 3cm (0.4 inches), seems somewhat sluggish, but it features elongated appendages resembling fingers of varying lengths.

These appendages are not used for waving or swimming; they are anatomical structures called ceratha, essentially serving as a secondary gill by extending the intestines and respiratory system to facilitate breathing.

Like many sea slug species, the Blue Dragon utilizes its ceratha as a weapon. They are notorious hunters, primarily targeting other blue-hued Neustons, including Portuguese man o’ war (Physalia physalis) and jellyfish-like creatures like blue buttons (Porpita porpita) and by-the-wind sailors (Velella velella).

Blue dragons can inject venom into these organisms without fear of being stung.

Remarkably, these sea slugs can recycle their prey’s toxins, maintaining them intact and incorporating them into their ceratha.

When threatened by predators, they can launch these toxins as a potent defense mechanism.

Modern challenges pose threats to Blue Dragons and their fellow Neuston inhabitants. A study conducted between Hawaii and California reveals that they inhabit the same remote regions of the infamous Pacific Ocean, including the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, where floating plastic debris accumulates due to swirling ocean currents.

One approach to combat this plastic pollution involves placing a net between two vessels to retrieve debris from the surface. However, this method could inadvertently capture a significant number of Neustons.

The complete ecological consequences of this method remain unclear, but it may have significant repercussions on the marine food web. These creatures serve as crucial food sources for a variety of marine species, such as sea turtles and seabirds.

Please email us to submit your questions at question@sciencefocus.com or message us on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram Page (please include your name and location).

Check out our ultimate Fun fact More amazing science pages

read more:

Source: www.sciencefocus.com