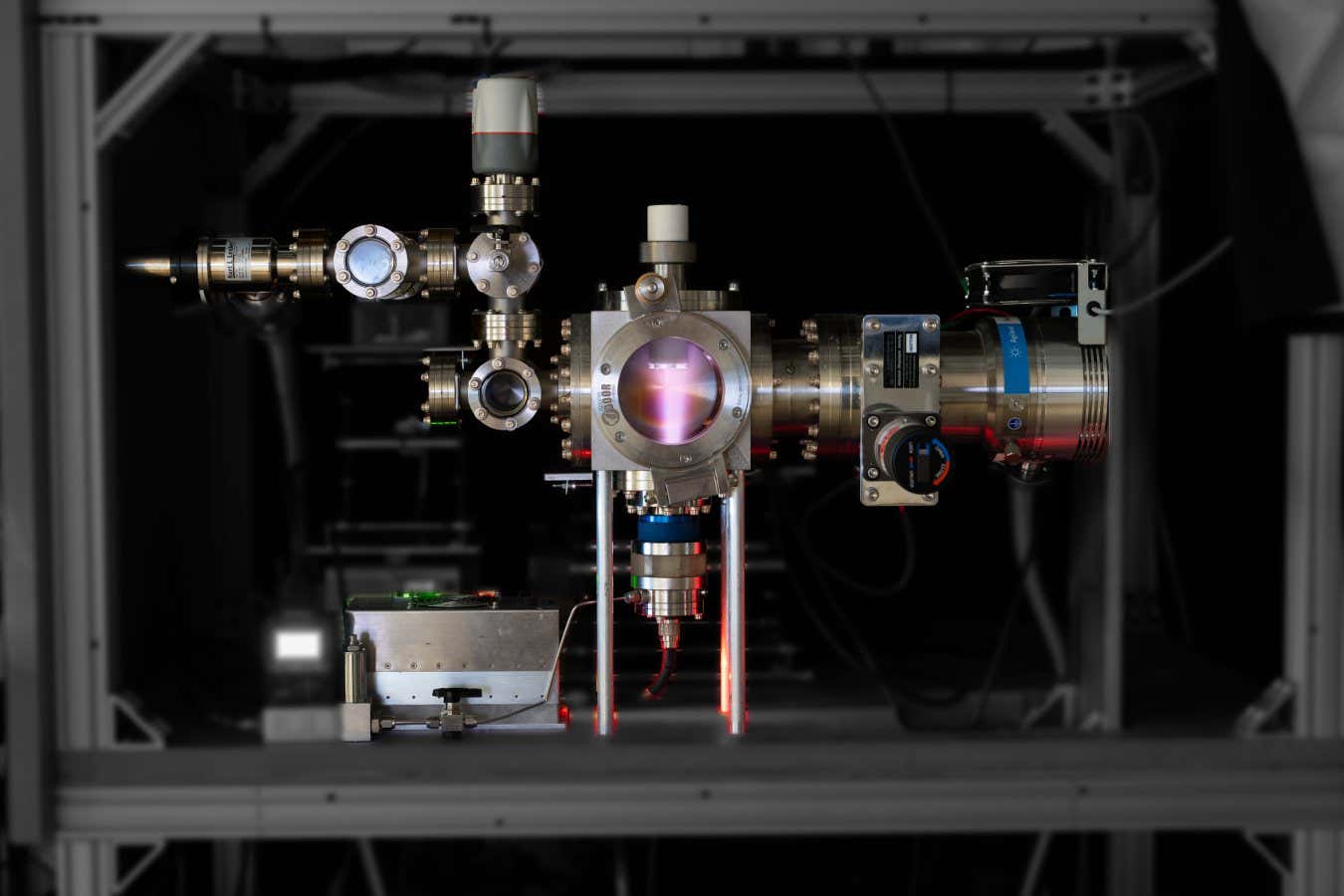

Thunderbird Fusion Reactor

Berlinguette Group, UBC

Cold Fusion, once a notorious name in the scientific community, is experiencing a resurgence. Researchers are revisiting earlier experiments that suggested room-temperature fusion, hinting at the potential for energy generation akin to that of the Sun, but without the extreme heat typically required. Although the initial claims were thoroughly scrutinized, recent iterations of this research have found ways to enhance fusion rates, even if they still fall short of producing usable energy.

Nuclear fusion involves merging atomic nuclei under extreme temperature and pressure, releasing energy in the process. This phenomenon naturally occurs in stars like our Sun, but replicating it on Earth for energy use has proven to be a significant challenge. Despite aspirations for commercial fusion reactors dating back to the 1950s, we haven’t yet managed to build one that yields more energy than it consumes.

The tide seemed to turn in 1989 when chemists Stanley Pons and Martin Fleischmann at the University of Utah reported that they had achieved nuclear fusion at room temperature using palladium rods submerged in water injected with neutron-rich heavy water and subjected to an electric current. This process generated unexpected heat spikes that surpassed predictions for standard chemical reactions, leading them to believe significant levels of nuclear fusion were occurring.

Dubbed Cold Fusion, this experiment captivated interest for its implication of a simpler, cleaner energy source compared to conventional hot fusion. However, the excitement quickly faded as researchers worldwide failed to replicate the observed heat anomalies.

Recently, Curtis Berlinguette and his team at the University of British Columbia have developed a novel tabletop particle accelerator, drawing inspiration from the original research conducted by Pons and Fleischmann.

“Cold fusion was dismissed back in 1989 due to the inability to replicate the findings. Our setup is designed for reproducibility, enabling verification by others,” Berlinguette explains. “We don’t claim to have discovered an energy miracle; our goal is to advance scientific understanding and provide reliable data to make fusion more attainable and interdisciplinary.”

Similar to the initial cold fusion experiment, the current research employs deuterium and palladium, which are hydrogen isotopes containing neutrons. The Thunderbird reactor utilizes a deuterium nucleus and a concentrated high-energy beam directed at a palladium electrode. This method prompts the palladium to absorb these high-energy particles and facilitates fusion by increasing the saturation of deuterium in the material.

To enhance fusion rates, the researchers incorporated an electrochemical device filled with deuterium oxide (heavy water). This device breaks down the heavy water into deuterium and oxygen, allowing the deuterium to be absorbed by the electrodes, boosting the quantity of deuterium available for fusion. “An essential takeaway from our 1989 experiment was the use of electrochemistry to introduce hydrogen fuel to the electrodes,” Berlinguette emphasizes.

As a result, the researchers noted a 15% increase in neutron production, correlating with a rise in fusion rates, though it only generates a billionth of a watt—far less than the 15 watts required to operate the device. “We’re just a few orders of magnitude away from powering your home with these reactors,” Berlinguette states.

While the experiment is notably inspired by the 1989 research, the current work indicates that the primary source of fusion comes from the powerful deuteron beam, rather than the electrochemistry proposed by Pons and Fleischmann. Anthony Ksernak from Imperial College London notes, “This is not an unknown phenomenon; it’s about colliding deuterium with a solid target and achieving what appears to be a fusion event,” noting the energy from the high-energy particles is equivalent to hundreds of millions of Kelvins.

Ksernak acknowledges that the 15% increase in deuterium saturation in palladium is modest, but he sees potential in experimenting with different metals for the electrodes in future research.

Berlinguette remains hopeful that the fusion rate can be elevated by redesigning the reactor. Recent unpublished work from a colleague suggests that merely altering the shape of the electrodes might yield a four-order magnitude increase in the fusion rate, though it would still fall short of the levels required for practical applications.

Even if higher fusion rates aren’t achieved, Berlinguette believes the electrochemical technique for enhancing deuterium loading in metals could be beneficial for developing high-temperature superconductors. Many promising superconducting materials, known for their zero electrical resistance and potential to transform global electrical systems, are metals that incorporate significant hydrogen amounts. Traditionally, creating these materials demands excessive pressure and energy; however, the electrochemical systems used in Thunderbird reactors could streamline the process with much less energy expenditure, according to Berlinguette.

Prepare to be amazed by CERN, the European Centre for Particle Physics. Here, researchers operate the renowned Large Hadron Collider situated near the picturesque Swiss city of Geneva. Topic:Cern and Mont Blanc, Dark and Frozen Matter: Switzerland and France

Source: www.newscientist.com