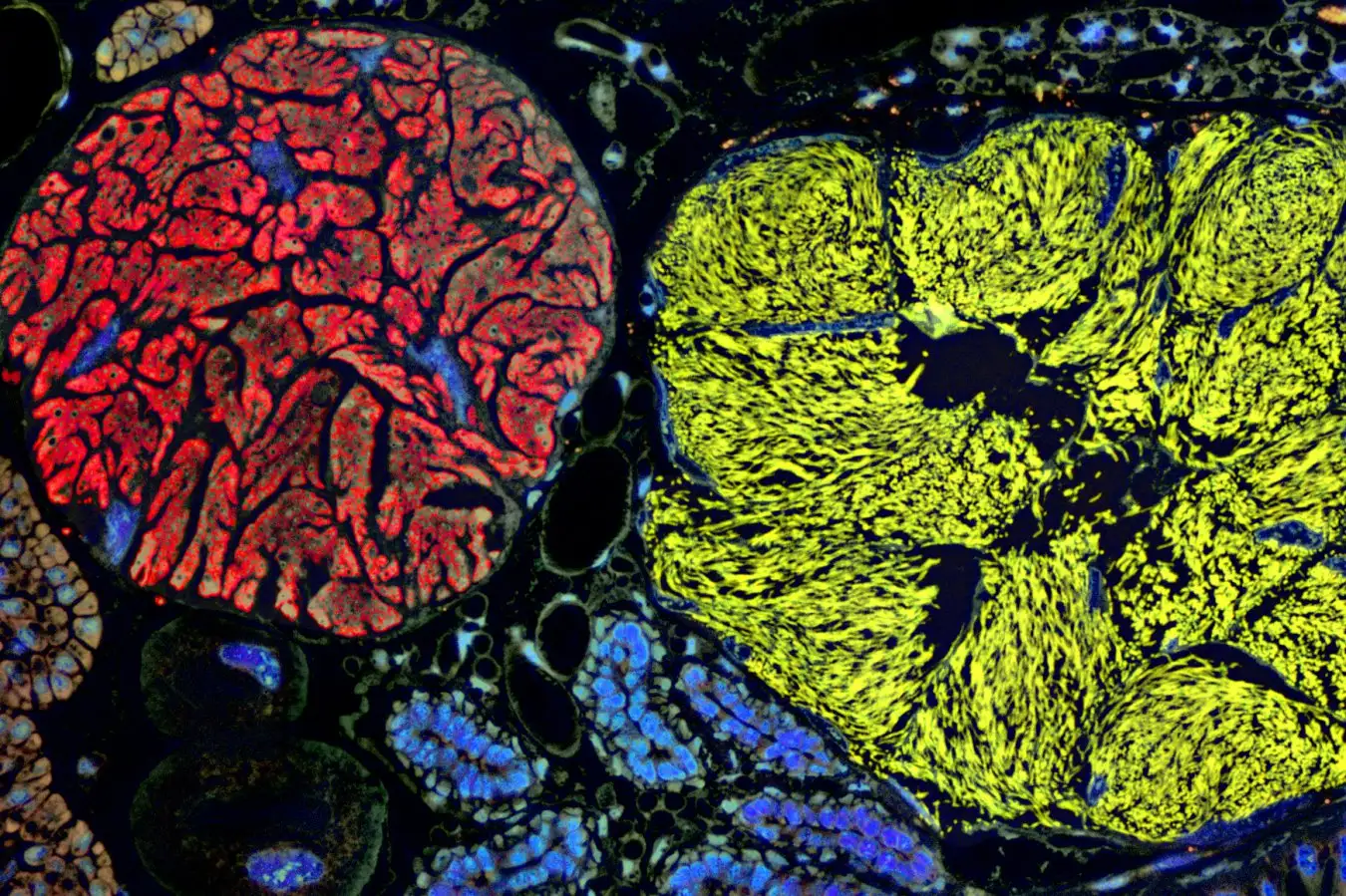

Symbiotic Bacteria Inside Insects: A Closer Look

Provided by: Anna Michalik et al.

Recent research reveals that symbiotic bacteria residing within insect cells possess the smallest genomes of any known organism. This groundbreaking discovery challenges the boundaries between organelles like mitochondria and highly simplified microorganisms.

“It’s challenging to define where this highly integrated symbiont ends and the organelle begins,” states Piotr Łukasik from Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Poland. “The line is exceedingly blurred.”

Planthoppers are unique insects that exclusively consume plant sap, relying on an ancient symbiotic relationship with bacteria to enhance their nutrition. Over millions of years, these microbes have adapted to inhabit specialized cells in the planthopper’s abdomen, generating essential nutrients that the insect’s sugary diet alone cannot provide. Many of these bacteria have become dependent on their hosts, having drastically reduced their genetic structures compared to their ancestors.

Łukasik and his team explored the evolution of this relationship and the minimization of bacterial genomes. They sampled 149 insects across 19 planthopper families, extracted DNA from their abdominal tissues, and sequenced this DNA to map the genomes of symbiotic bacteria like Vidania and Sulcia.

These bacterial genomes are notably small, with a total length of under 181,000 base pairs. In contrast, the human genome spans several billion base pairs.

Vidania, with its genome measuring a mere 50,000 base pairs, holds the record for the smallest known form of life. Previously, Nasuia, a symbiotic bacterium from leafhoppers, held this title with just over 100,000 base pairs.

To put this in perspective, Vidania‘s genome size is comparable to non-living viruses, such as the COVID-19 virus, which has a genome of about 30,000 base pairs. Remarkably, Vidania contains only around 60 protein-coding genes, the fewest recorded.

Planthoppers Depend on Symbiotic Bacteria for Nutrients

Provided by: Anna Michalik et al.

These bacteria have co-evolved with their insect hosts for approximately 263 million years and have independently developed very small genomes within two distinct categories of planthoppers. Notably, one of their primary functions is producing the amino acid phenylalanine, crucial for strengthening insect exoskeletons.

Research suggests that significant gene loss may occur when insects consume new food sources rich in nutrients previously supplied by bacteria or when other microbes colonize and assume these roles.

The characteristics of these highly reduced bacteria bear a resemblance to mitochondria and chloroplasts—energy-producing organelles in plants and animals that evolved from ancient bacteria. Symbiotic bacteria, like organelles, live inside host cells and are transmitted across generations.

“‘Organelle’ is a term open to interpretation, and it’s acceptable to classify these entities as organelles,” states Nancy Moran from the University of Texas at Austin, who was not part of the study. “However, the distinctions between them and mitochondria or chloroplasts remain clear.”

Mitochondria, which have a longer evolutionary history of over 1.5 billion years, only contain about 15,000 base pairs in their genomes.

Łukasik posits that these bacteria and mitochondria function along different points on an evolutionary “gradient of dependence” on their hosts, hinting that even smaller symbiont genomes may still be undiscovered.

Topic:

Source: www.newscientist.com