Contemporary artificial intelligence (AI) models are vast, relying on energy-hungry server farms and operating on billions of parameters trained on extensive datasets.

Is this the only way forward? It seems not. One of the most exciting prospects for the future of machine intelligence began with something significantly smaller: the minute worm.

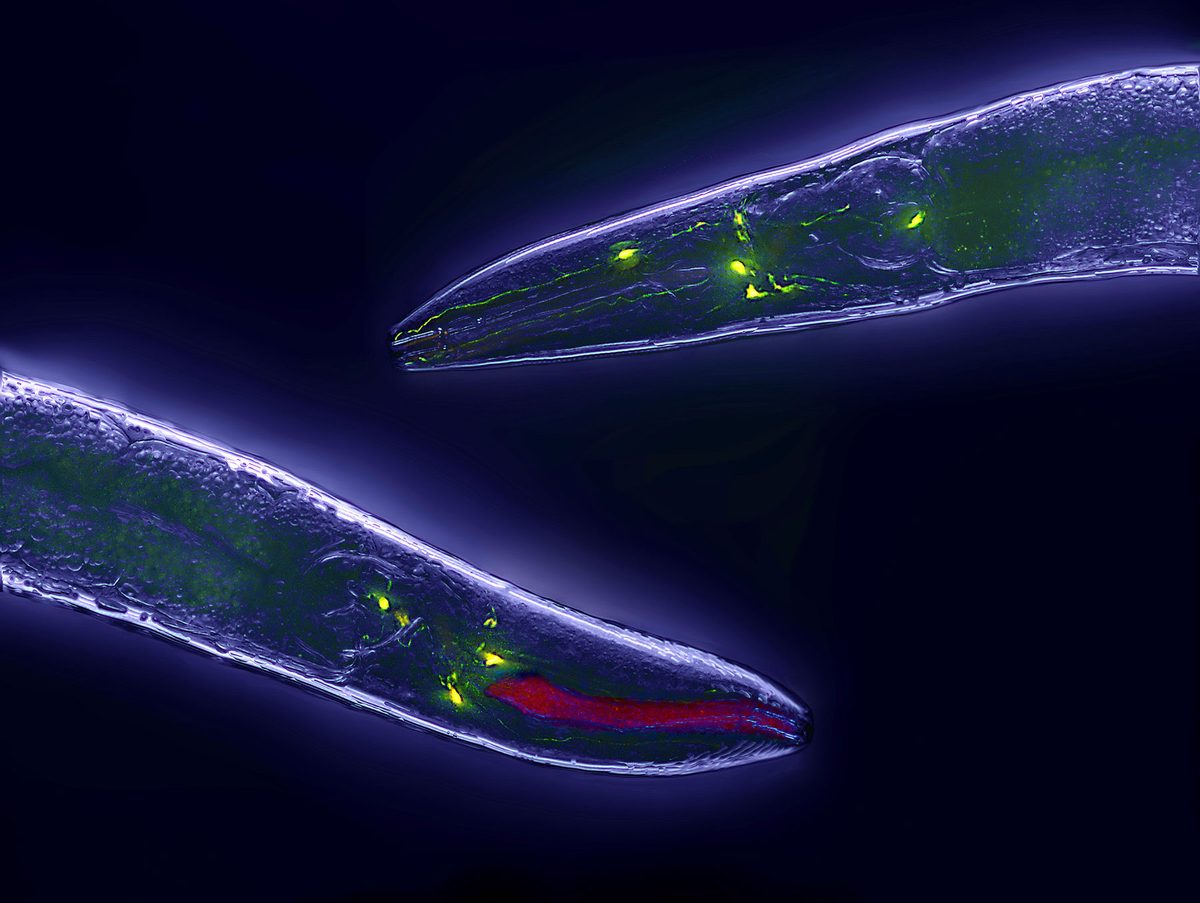

Inspired by Caenorhabditis elegans, a tiny creature measuring just a millimeter and possessing only 302 neurons, researchers have designed a “liquid neural network,” a radically different type of AI capable of learning, adapting, and reasoning on a single device.

“I wanted to understand human intelligence,” said Dr. Ramin Hassani, co-founder and CEO of Liquid AI, a pioneering company in this mini-revolution, as reported by BBC Science Focus. “However, we found that there was minimal information available about the human brain or even those of rats and monkeys.”

At that point, the most thoroughly mapped nervous system belonged to C. elegans, providing a starting point for Hassani and his team.

The appeal of C. elegans lay not in its behavior, but in its “neurodynamics,” or how its cells communicated with one another.

The neurons in this worm’s brain transmit information through analog signals rather than the sharp electrical spikes typical of larger animals. As nervous systems developed and organisms increased in size, spiking neurons became more efficient for information transmission over distances.

Nonetheless, the origins of human neural computation trace back to the analog realm.

For Hassani, this was an enlightening discovery. “Biology provides a unique lens to refine our possibilities,” he explained. “After billions of years of evolution, every viable method to create efficient algorithms has been considered.”

Instead of emulating the worm’s neurons one by one, Hassani and his collaborators aimed to capture their essence of flexibility, feedback, and adaptability.

“We’re not practicing biomimicry,” he emphasized. “We draw inspiration from nature, physics, and neuroscience to enhance artificial neural networks.”

read more:

What characterizes them as “liquid”?

Conventional neural networks, like those powering today’s chatbots and image generators, tend to be very static. Once trained, their internal connections are fixed and not easily altered through experience.

Liquid neural networks, however, offer a different approach. “They are a fluid that enhances adaptability,” said Hassani. “These systems can remain dynamic throughout computation.”

To illustrate, he referenced self-driving cars. When driving in rain, adjustments must be made even if visibility (or input data) becomes obscured. Thus, the system must adapt and be sufficiently flexible.

Traditional neural networks operate in a strictly unidirectional, deterministic fashion — the same input always results in the same output, and data flow is linear within the layer. While this is a simplified view, the point is clear.

Liquid neural networks function differently: neurons can influence one another bidirectionally, resulting in a more dynamic system. Consequently, these models behave stochastically. Providing the same input twice may yield slightly varied responses, akin to biological systems.

“Traditional networks take input, process it, and deliver results,” stated Hassani. “In contrast, liquid neural networks perform calculations while simultaneously adjusting their processing methods with each new input.”

The mathematics behind these networks is complex. Earlier versions were slow due to the reliance on intricate equations requiring sequential resolution before yielding an output.

In 2022, Hassani and his team published a study in Nature Machine Intelligence, introducing an approximate way to manage these equations without heavy computation.

This innovation significantly enhanced the liquid model’s speed and efficiency while preserving the biological adaptability that conventional AI systems often lack.

More compact, eco-friendly, and intelligent

This adaptability allows liquid models to store considerably more information within smaller infrastructures.

“Ultimately, what defines an AI system is its ability to process vast amounts of data and condense it into this algorithmic framework,” Hassani remarked.

“If your system is constrained by static parameters, your capabilities are limited. However, with dynamic flexibility, one can effectively encapsulate greater intelligence within the system.”

He referred to this as the “liquid method of calculation.” Consequently, models thousands of times smaller than today’s large language models can perform comparably or even exceed them in specific tasks.

Professor Peter Bentley, a computer scientist at University College London, specializing in biologically-inspired computing, noted that this transformation is vital: “AI is presently dominated by energy-intensive models relying on antiquated concepts of neuron network simulation.”

“Fewer neurons translate to a smaller model, which reduces computational demand and energy consumption. The capacity for ongoing learning is crucial, something current large models struggle to achieve.”

As Hassani stated, “You can essentially integrate one of our systems into your coffee machine.”

“If it can operate within the smallest computational unit, it can be hosted anywhere, opening up a vast array of opportunities.”

AI that fits in your pocket and on your face

Liquid AI is actively developing these systems for real-world application. One collaboration involves smart glasses that operate directly on users’ devices, while others are focused on self-driving cars and language translators functioning on smartphones.

Hassani, a regular glasses wearer, pointed out that although smart glasses sound appealing, users may not want every detail in their surroundings sent to a server for processing (consider bathroom breaks).

This is where Liquid Networks excel. They can operate on minimal hardware, allowing for local data processing, enhancing privacy, and reducing energy consumption.

This also promotes AI independence. “Humans don’t depend on one another for function,” Hassani explained. “Yet they communicate. I envision future devices that maintain this independence while being capable of sharing information.”

Hassani dubbed this evolution “physical AI,” referring to intelligence that extends beyond cloud settings to engage with the physical realm. Realizing this form of intelligence could make the sci-fi vision of robots a reality without needing constant internet access.

However, there are some limitations. Liquid systems only function with “time series” data, meaning they cannot process static images, which traditional AI excels at, but they require continuous data like video.

According to Bentley, this limitation is not as restrictive as it appears. “Time series data may sound limiting, but it’s quite the opposite. Most real-world data has a temporal component or evolves over time, encompassing video, audio, financial exchanges, robotic sensors, and much more.”

Hassani also acknowledged that these systems aren’t designed for groundbreaking scientific advancements, such as identifying new energy sources or treatments. This research domain will likely remain with larger models.

Yet, that isn’t the primary focus. Instead, this technology aims to render AI more efficient, interpretable, and human-like while adapting it to fit various real-world applications. And it all originated from a small worm quietly moving through the soil.

read more:

Source: www.sciencefocus.com