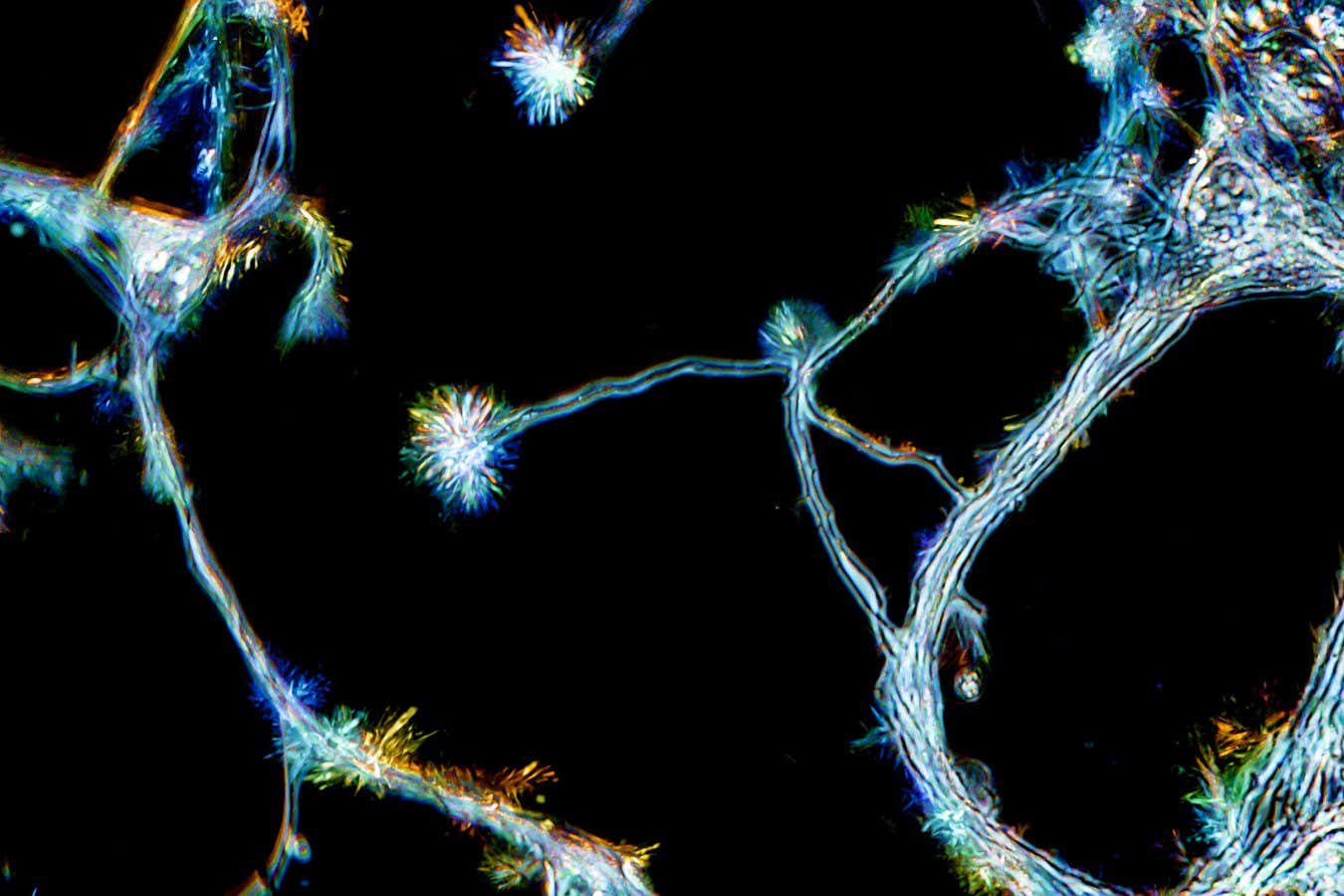

Generates brain cells from the hippocampus that proliferate in culture

Arthur Chien/Science Photo Library

The ongoing debate about whether adults can produce new brain cells takes a new turn, as evidence increasingly supports that they indeed can. This revelation addresses one of neuroscience’s most disputed questions and raises hopes that this knowledge could be used in treating conditions like depression and Alzheimer’s disease.

Neurons are produced via a process known as neurogenesis, which occurs in both children and adults, as shown in research on mice and macaques. This involves stem cells generating progenitor cells, which multiply and eventually develop into immature neurons that mature over time.

Earlier studies have indicated the presence of stem cells and immature neurons in the hippocampus of adult humans. This brain area, crucial for learning and memory, is a primary site for neurogenesis in younger humans and some adult animals. However, progenitor cells have not yet been detected in adult human brains. “This link was overlooked. It forms a central argument for the emergence of new neurons in the adult human brain,” states Evgenia Salta from the Netherlands Institute of Neuroscience, who was not involved in the latest research.

To establish this link, Jonas Frisen and his team at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden developed a machine learning model capable of accurately identifying progenitor cells. They used hippocampal samples from six young children, donated by their parents for research post-mortem.

The researchers trained an AI model to recognize progenitor cells based on the activity of about 10,000 genes. “In childhood, these cells’ behavior closely resembles that of precursor cells in mice, facilitating their identification,” explains Frisen. “[The idea is] to use molecular fingerprints of childhood progenitor cells to find equivalents in adults.”

To validate the model, the team identified progenitor cells in hippocampal samples from young mice. The model correctly identified 83% of the progenitor cells and misclassified other cell types as progenitor cells in less than 1% of cases. In a further test, the model accurately predicted that progenitor cells were nearly absent in adult human cortical samples, a brain area devoid of evidence supporting neurogenesis in humans.

“They validated their models effectively by transitioning from data on human children to mice and then to adult humans,” says Sandrine Thuret from King’s College London.

With this validation in hand, the researchers can check for neurogenesis in human adults by identifying 14 hippocampal progenitor cells from individuals aged 20 to 78 at the time of their passing.

Crucially, the researchers first introduced a method to enhance the likelihood of detecting progenitor cells. Previous studies have indicated that these cells are extremely rare in adults. The team utilized antibodies to select brain cells that were actively dividing at the time of death, including non-neuronal cells such as immune cells and progenitor cells. This helped filter out common cell types that do not divide, like mature neurons, making rare progenitor cells easier to identify.

Subsequently, they organized the genetic activity data related to these dividing cells into models. “They were enriched due to the selected cells,” remarks Kaoru Song at the University of Pennsylvania. Previous research lacked this approach, he adds.

The team successfully identified progenitor cells in nine donors. “It is well established that environmental and genetic factors in rodents affect how neurogenesis occurs, so I suspect variations in humans may also be attributed to these factors,” Frisen notes.

The findings strongly indicate the presence of adult neurogenesis, according to Thuret, Song, and Salta. “We are adding this missing piece, which significantly advances the field,” Salta states.

“Neurons originate from cell division occurring in adulthood, and that is what this study definitively establishes,” Thuret comments.

Thuret suggests the possibility of examining variations in neurogenesis among adults with brain-affecting conditions such as depression or Alzheimer’s disease. She speculates that medications promoting this process could alleviate symptoms.

However, John Arellano from Yale University cautions that even if adults produce new brain cells, they may be too few in number to be therapeutically beneficial. Thuret, however, believes this is unlikely to create issues. “In mice, a small number of new neurons can significantly impact learning and memory,” she asserts.

Topic:

Source: www.newscientist.com