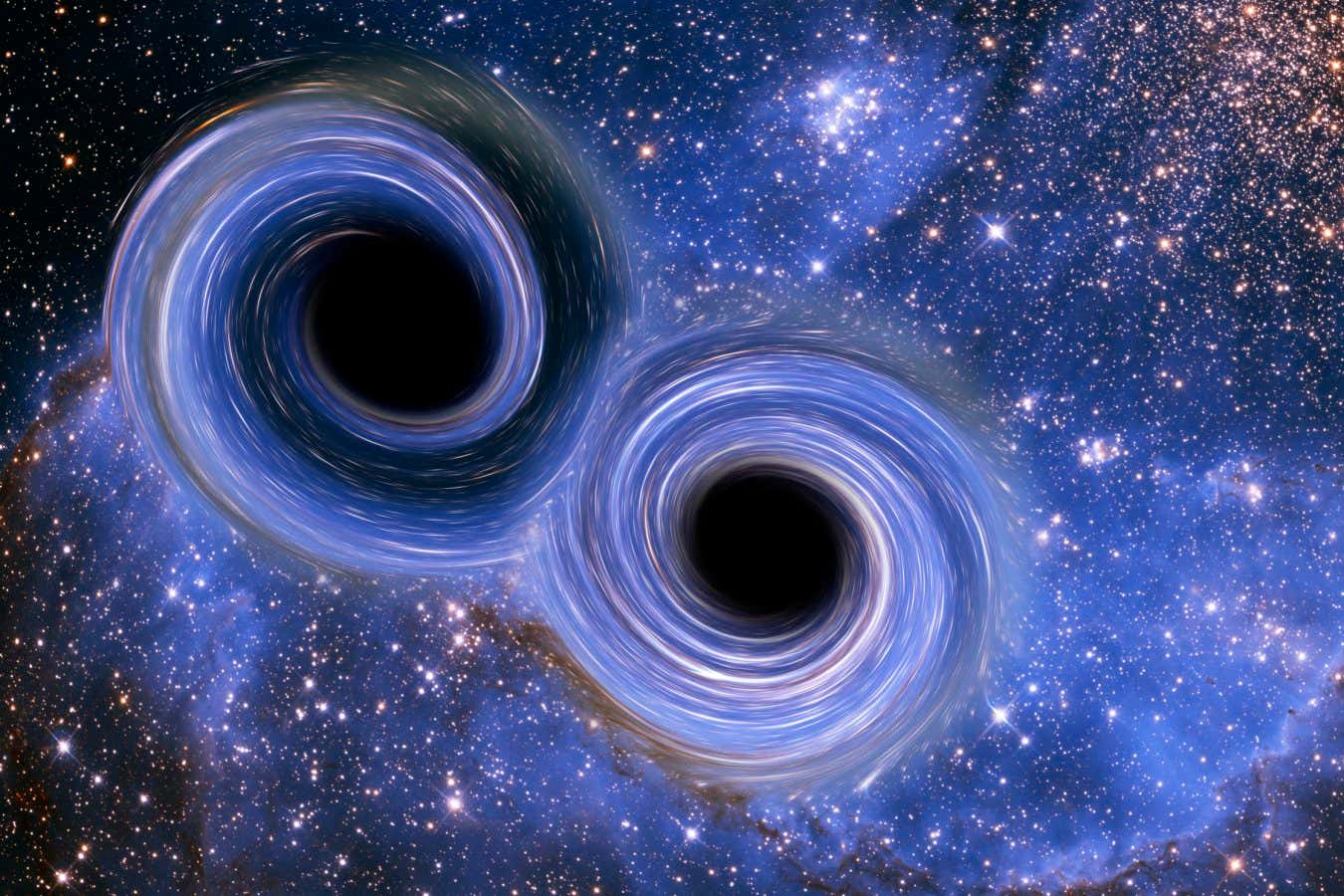

Gravitational waves result from colliding black holes

Victor de Schwanberg/Science Photography Library

Researching the universe can be enhanced by AI created by Google DeepMind. With an algorithm capable of diminishing unwanted noise by as much as 100 times, the Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO), equipped with laser interferometers, can identify specific black hole types that are affecting our separation.

LIGO aims to detect gravitational waves generated when entities like black holes spiral and collide. These waves traverse the universe at light speed, yet the spacetime fluctuations are minimal—10,000 times smaller than an atomic nucleus. Since its initial detection a decade ago, LIGO has recorded signals from nearly 100 black hole collisions.

The experiment comprises two U.S. observatories, each with two perpendicular arms measuring 4 km. A laser is directed down each arm and bounced off precise mirrors, where an interferometer compares the beams. As gravitational waves pass through, the lengths of the arms fluctuate slightly, and these changes are meticulously documented to help visualize the signals’ origins.

However, achieving such precision is challenging, as even distant ocean waves or clouds can interfere with measurements. This noise can overwhelm the signal, rendering some observations unfeasible. To counterbalance this noise and accurately adjust the mirrors and other equipment, numerous critical tweaks are essential.

Lana Adhikari from the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena stated that his team has collaborated with DeepMind to innovate new AI methods. He mentions that even automating these adjustments can sometimes introduce noise. “That control noise has puzzled us for decades. All aspects in this space are hindered,” Adhikari explains. “How can you stabilize a mirror without creating noise? If left uncontrolled, the mirror tends to oscillate unpredictably.”

Laura Nuttall from the University of Portsmouth, UK, was involved in manually executing these adjustments at LIGO. “Changing one element causes a cascading effect; one change leads to another,” she points out. “It feels like an endless cycle of fine-tuning.”

DeepMind’s new AI, known as Deep Loop Shaping, aims to minimize noise by making up to 100 adjustments to LIGO’s mirrors. The AI is trained via simulations before being implemented in real-world scenarios, focusing on achieving two main objectives: limiting the number of adjustments it performs. “Over time, as it repeatedly operates, it’s like conducting hundreds or thousands of trials in a simulation. The controller learns what strategies work and identifies the best approach,” says Jonas Buchli from DeepMind.

Alberto Vecchio from the University of Birmingham, UK, expressed enthusiasm for the AI’s role in LIGO but mentioned that many challenges remain. The AI currently operates effectively for only an hour under real conditions, necessitating longer-term validation. Additionally, it’s only been applied to one control aspect, while many hundreds, if not thousands, of factors could assist in stabilizing the mirrors.

“This is clearly an initial step, but it’s certainly a fascinating one. There’s considerable scope for significant advancement,” Vecchio remarked.

If similar enhancements could be replicated elsewhere, it’s possible to detect medium-sized black holes—those around 1,000 times the mass of our sun—a category that has yet to see confirmed observations. Improvements are typically seen with the low-frequency gravitational waves generated by large bodies, where noise can obscure the signals.

“We’ve observed black holes up to 100 solar masses and more than a million solar masses in galaxies. What’s out there in between?” Vecchio pondered. “There’s a perception that black holes exist across a spectrum of masses, yet clear experimental evidence remains elusive.”

Nuttall commented that this new methodology could enhance identification of known black hole types. “This appears quite promising,” she stated. “I’m thrilled about this development.”

Topic:

Source: www.newscientist.com