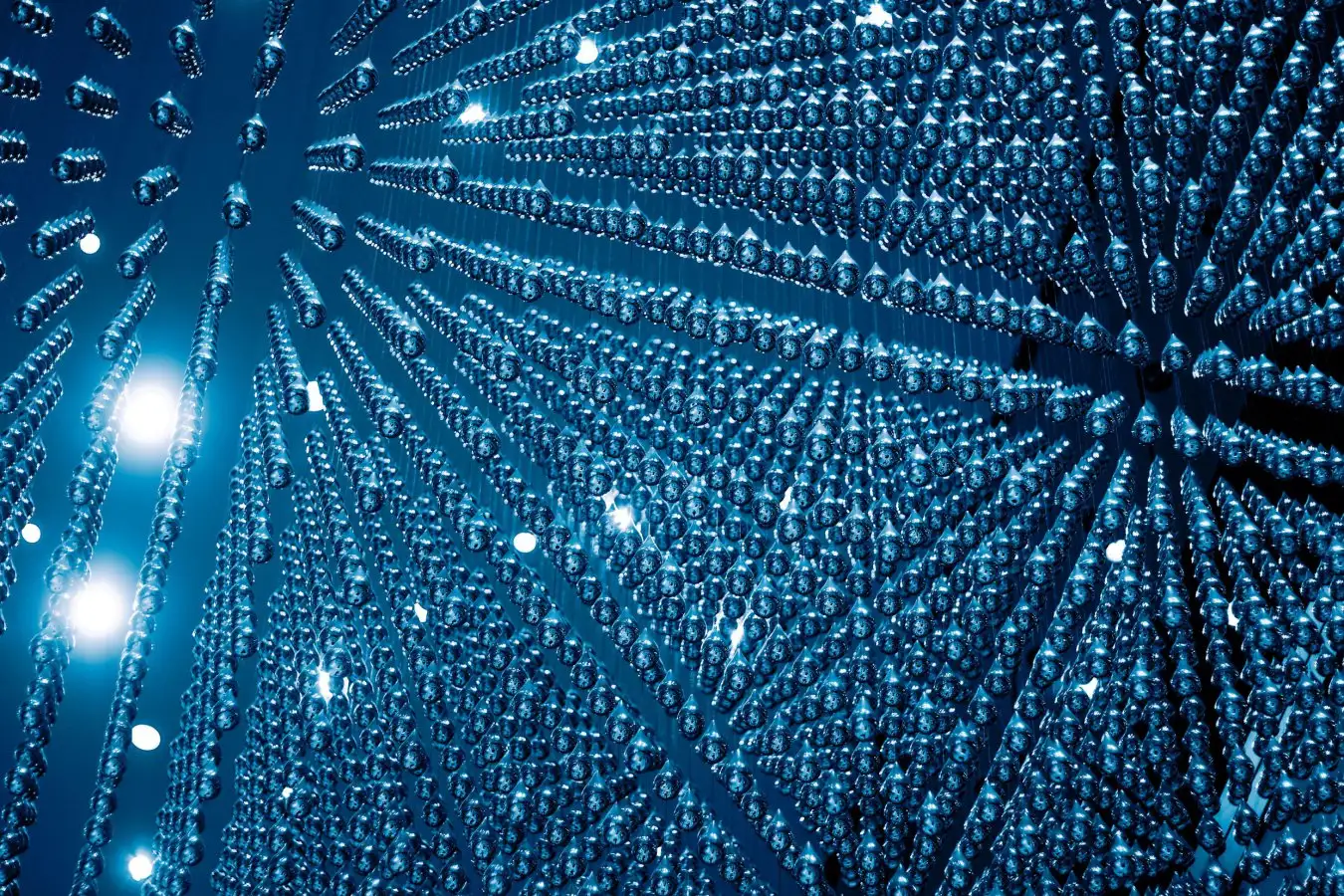

Electrons Interacting and Causing Friction

High quality stock/Alamy

Even the smoothest surfaces can exhibit friction due to electron interactions. However, recent advancements present a technique for reducing or completely eliminating this electronic friction, empowering the development of more efficient and durable devices.

Frictional forces, in various contexts, can hinder movement, waste energy, and can be beneficial in everyday tasks like walking or striking a match. In mechanical systems, such as engines, friction not only expends energy but also accelerates wear, necessitating the use of lubricants and surface treatments. Nevertheless, as every object harbors numerous electrons that interact, some degree of friction may always exist regardless of mitigation strategies.

According to Xu Zhiping, researchers from Tsinghua University in China have developed an innovative method to manage this “electronic friction.” Their apparatus consists of dual layers of graphite paired with a semiconductor crafted from molybdenum and sulfur or boron and nitrogen.

These materials excel as solid lubricants, showcasing near-zero mechanical friction when in motion against each other. This focus allowed researchers to explore a less apparent factor: electronic friction, which contributes to energy loss during the layers’ movement. Xu elaborated, “Even with entirely smooth surfaces, mechanical activity can disturb the ‘sea’ of electrons within the material.”

To confirm their focus on electronic friction, the team initially analyzed how the electronic state of the semiconductor reacted to energy depletion during sliding. They subsequently explored various methods for controlling this phenomenon.

By applying pressure to their device, they succeeded in halting the ocean of electrons by allowing the electrons between layers to share states, minimizing energetically costly interactions. Additionally, introducing a “bias voltage” enabled them to fine-tune the motion of these electrons.

By adjusting the voltage across different segments of the device, researchers could influence electron flow, effectively reducing electronic friction and allowing for a dynamic control mechanism instead of a simple on-off switch.

Jacqueline Krim noted that the initial study on electron friction dates back to 1998 when her North Carolina State University team utilized superconducting materials—perfect electrical conductors at extremely low temperatures—to observe energy loss. Research has since evolved, offering new avenues for modulation without necessitating material replacement or additional lubricants, she commented.

Krim envisions a scenario akin to adjusting the friction of your shoe soles via a smartphone app when transitioning from icy sidewalks to carpeted rooms. “Our objective is real-time remote control, eliminating downtime and material waste. Achieving this goal necessitates materials that react to external magnetic fields producing the desired levels of friction,” she explained.

Xu acknowledged the complexities involved in managing all forms of friction within a device, noting that a rigorous mathematical model correlating these frictions is yet to be established. Nevertheless, he expressed optimism regarding their findings, suggesting that if electronic friction primarily drives energy waste and wear, their approach could hold considerable promise.

Topic:

Source: www.newscientist.com